1882 Delegations

President:

Chester A. Arthur

Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1882:

Hiram Price (May 6, 1881 – March 27, 1885)

Jan. 9, 1882: Daily Critic (DC): [unid.]

An Indian delegation in charge of Representative Joyce, of Vermont, called to pay their respects to the President.

Jan. 14, 1882: Boston Journal: [Seneca]

The Seneca Indians.

A delegation of Seneca Indians, residing in Western New York, arrived here to-day for the purpose of securing amendments to bills pending before congress in which it is proposed to allot lands in severalty in Indian reservations. These Senecas desire to except their lands from the operation of the proposed law. The tribe, numbering about 2000, own more than 50,000 acres of land, situated in Erie, Chatauqua and Cattaraugus counties.

Jan. 26, 1882: Dallas Weekly Herald: [Miami]

Washington, January 18.—

A delegation of Miami Indians, from the Indian Territory, are now here endeavoring to secure legislation looking to the allotment of their lands in that Territory.

Feb. 9, 1882: Worcester Daily Spy [Worcester, Mass.]: [N. Arap., Shoshoni]

An Indian Delegation.

Carlisle, Pa. Feb. 8—Agent Hatten of the Northern Arapahoes and Shoshone agency, Wyoming, with his chiefs Black Coat [sic], White Horse, Iron, Sharpnose [sic] and Little Wolf, who have been visiting the Indian school since Friday, left this morning for Washington, Chief Black Coat spoke for the party, endorsing the school and urging that children to learn all that the whites knew before they return. These men all have children at the school.

Feb. 10, 1882: Evening Star: [Arapaho]

Arapahoe Chiefs at the Interior Department.

Black-Cole, Sharp Nose and others of thee Arapahoe delegation from Wyoming, paid their respects to Secretary Kirkwood this morning. They are fine looking Indians, in full native costume. The tribes they represent have been at peace with the whites for many years, but have frequently joined the soldiers in subduing the hostiles. In consequence of these friendly relations, several of the chiefs have children at the Carlisle school, but the Indians at home, numbering about two thousand, have made little advancement. The Secretary has sescured from the chiefs a promise that they will co-operate with the department in getting the Indians to begin farming and stock raising, which they say their people are now ready to undertake. Their language is apparently destitute of [illeg.] and in speaking there is scarcely any perceptible movement of the lips or muscles of the face.

Feb. 11, 1882: Worcester Daily Spy: [Arapaho]

Indian Visitors.

Five of the Arapaho Indian chiefs called upon the secretary of the Interior today, and had quite a long conversation with him touching their affairs. The Indians are highly pleased at the progress of their children at Carlisle, Pa., in what they call “the white man’s road.” Secretary Kirkwood talked to them at some length upon the advantages to be gained by cultivating land individually and raising their own stock. He was listened to attentively by the chiefs who were evidently favorably inclined to such a course.

Feb. 12, 1882: Boston Herald: [Arapaho]

A delegation of Arapahoe Indians paid its respects to the President this afternoon.

Feb. 15, 1882: Denver Republican: [Arapaho]

The Arapahoe Indian delegation held a conference with Secretary Kirkwood yesterday.

Feb. 15, 1882: Cleveland Leader: [Arapaho]

They Want Houses.

Secretary Kirkwood held a second conference today with the Arapahoe Indian chief Black coal. The principal chief, asked if they could have houses “like white men,” and the Secretary replied that if they could build them for themselves, they would be furnished with the necessary materials. Secretary Kirkwood stipulated, however, that they must not erect their tepees in front of houses, and use the latter for stables, as had been asserted of other tribes.

Feb. 15, 1882: San Francisco Chronicle: [Arapaho]

A Conference with Arapahoes.

Secretary Kirkwood held a second conference to-day with the Arapahoe Indian chiefs. They had listened eagerly last week to the Secretary’s remarks in favor of their settlement, and today they said they were convinced that such a course would be to their advantage. The principal chief asked if they could have houses like white men, to which the Secretary replied that if they would build them for themselves they would be furnished the necessary materials. Secretary Kirkwood stipulated, however, that they must not erect their tepees (or lodges) in front of the houses and use the later for stables, as had been asserted of other tribes. These Indians leave for Wyoming in a few days.

Feb. 19, 1882: Kalamazoo Gazette: [unid.]

A long report on the status of Indian Territory has been transmitted to congress by the secretary of the interior. It asserts that there are no lands open to settlement or entry, the tracts in the territory to which the government holds title being reserved by treaty stipulations. A proposition that the criminal laws of the United States be extended over their lands has been made to the Indian delegations now in Washington, and will evidently meet their approval.

[This article appears in several other small newspapers – not copied]

March 4, 1882: Evening Star: [Zuni]

The Zuni Indians In The City.—The report that a delegation of Zuni Indians from New Mexico, headed by Dr. Cushing, of the U.S. geological survey, would hold a conference with the Secretary of the Interior and Commissioner of Indian Affairs to-day, is a mistake. There is a delegation of those Indians in the city, but they have come east, it appears, for the purpose of performing some peculiar religious ceremony on the seacoast. They were not called here by the Indian bureau, and the latter has no official connection with their visit. The delegation called at the Indian office and asked that their expenses while on their present trip be allowed and paid by the department, but Commissioner Price decided that he had no authority to make any such allowance.

March 4, 1882: Boston Journal: [Zuni]

The sensation to which the good people of New England are about to be treated, as announced by telegraph from the West, of seeing a delegation of Zuni Indians celebrating an alleged religious rite in sight of the ocean from Plymouth Rock, is likely to cause some alarm, Popular tradition is apt to regard the religious rites of Indians as in some way connected with scalps, and rumor has it that the people of Plymouth are negotiating for barricades for their front doors, and drilling loop-holes in the upper stories, of their residences. Popular alarm is not likely to be allayed by the statement that the tribe is addicted to agriculture, and that one object of the visit to the East is to study the bearings of baked beans and pumpkin pie upon the civilization of the pale-faces. Cautious citizens of Plymouth will not be misled by such reports, but will continue to sit up nights and run bullets pick [illeg.] and load cartridges. At this time of day one cannot think with patience of savages dancing scalp-dances and trundling war whoops on the ground made sacred by the landing of the Pilgrim Fathers.

March 6, 1882: Cincinnati Daily Gazette: [Zuni]

A delegation of Zuni Indians from New Mexico are here on their way to the Eastern Seacoast, where they propose to perform some religious rites. They have an eye to business, however, as they at once called at the Indian Office and asked that the expenses of their trip be paid by the government. The Indian Commissioner informed them that he had no authority to make such allowance, which somewhat dampened their religious ardor.

March 9, 1882: Evening Star: [Hopi, Zuni]

Lectures:

Mr. Frank H. Cushing Will deliver a Lecture on “Experiences Among the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico.” In the Lecture Room of the National Museum, on Friday Evening, the 10th Inst., at 8 o’clock. Admission free, and Ladies and Gentlemen are cordially invited to attend.

A delegation of Zuni and Moqui Indians will be present in full costume. M9-2t [May 9, 2 times]

March 10, 1882: Evening Star; [Zuni]

Amusements, etc.

Mr. Frank H. Cushing will deliver a free lecture on “Experiences Among the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico” in the lecture room of the National Museum this evening.

March 11, 1882: Evening Star: [Zuni, Hopi]

The Zuni Race.

Experiences of Mr. Frank H. Cushing Among a Strange People—His Lecture at the National Museum.

The lecture hall of the National Museum building was filled last night to hear Mr. Frank H. Cushing, of the Smithsonian institution, relate his experiences among the Zuni Indians of New Mexico, who, despite their constant contact for 350 years with European civilization, as represented by the old Spanish explorers and Franciscan monks, and the modern settler, have preserved their savage individuality and their ancient traditions, forms and customs uncorrupted. The six Zuni Indians, with barbarous names, brought by Mr. Cushing, from their distant homes to see the “Ocean of the sunrise,” were introduced to the audience, and sat in grim majesty, arrayed in all the splendor of striped blankets and red head bands during the entire lecture. At its close two of the Indians made brief speeches of greeting, which were interpreted by Mr. Cushing, the whole party united in a low song or chant, and the youngest of the party gave a specimen of a Zuni dance; keeping time with a sort of chant hummed by his brothers. The dancer was a Moqui who has been adopted into the tribe of Zuni.

The Zuni People.

Mr. Cushing said the Zunis were low in stature, with well developed limbs, and a great diversity of facial expression. The women are shorter and fairer. The children are, perhaps, the most beautiful children in the world, but as they grow old get ugly, like other Indians. In disposition the Zunis are peaceable and gentle, it being a rule with them to be always careful and considerate in speech. Intellectually they are the brightest Indians Mr. Cushing ever met, but had an element of conservatism about them that permited them taking readily to new notions. Until he visited them two years and six months ago, he said, no stranger had ever been admitted to their mysterious orders and sacred temples. Mr. Cushing gave a very interesting account of his life with them, and the way in which he had gradually gained their confidence and love. At first he was received with suspicion, and was constantly watched while taking notes and sketches. He made his way to their hearts by making presents to their children. The names given him from time to time during his stay, the first denoting suspicion and ridicule, indicated the gradual progress he made into their full confidence.

Adopted into the Tribe.

He was at first adopted by the high priest as his son. Still the members of the tribe eyes him suspiciously, and resisted his investigations. He had taken sketches of many of the minor dances and ceremonials, and so offended many members of the tribe that it was resolved to intimidate him. So a grand war dance was arranged, which was the most magnificent ceremony he had at the time witnessed. At a certain moment two warriors rushed towards Mr. Cushing with their clubs, giving him an intimation for the first time that he was the object of the warlike attentions he had witnessed. Mr. Cushing, taking a knife which he carried in his sketch-book into his hand, laid it at his feet, and laughed. The warriors, hesitated, then rushed back shouted “Ke-hay,” and disappeared. They soon returned, dragging with them a large yellow dog, which was slain, one of the warriors extracting the heart and liver, and proceeding to eat it. The meaning of this was that they had discovered that Mr. Cushing was a “Ke-hay,” or spiritual friend. From that time his progress towards full communion with members of the tribe was steady. He resisted the proposition to have his ears pierced for seven months, but finally yielded. Having gained some acquaintance with the language, he asked to have the traditions of the tribe told to him.

The Homer of the Zunis.

A council was held in his room, and an old blind white-haired man, whom he had seen wandering about the pueblo, as led in. This old man—a sort of Zuni Homer—then began a recital, rhythmical and metrical in proportions, which composed the Genesis of the order. It could not all be sung in one night. The arrangement of this epic was in books, chapters and paragraphs. It convinced Mr. Cushing that he must devote years to the Zuni Indians. In the course of eight or nine months he was able to speak their language with tolerable fluency. He then investigated their esoteric orders, of which there are 13, one, however, the highest of all—

The Order of the Bow—

Being more strictly esoteric than the others. Mr. Cushing aimed to become a member of the Order of the Bow, and after securing an Apache scalp—as such a trophy was necessary for admission to the sacred mysteries of the order—he was at last admitted, having first been adopted into the Clan of the Parrot, the most aristocratic of the families or clans of the Zunis. The ceremonies of initiation, which were carried on with great solemnity, lasted many days. Mr. Cushing gave a very interesting account of the social divisions among the interesting people with whom he proposes yet to spend some years of his life. In reply to questions, he said their views of the future life are very much like those of modern spiritualists. They believe that their people are nearer God than any other people. When one of them was taken upon a locomotive by Mr. Cushing, he said: “Your people are Gods, only they have to eat.” Mr. Cushing has been elevated to the rank of war chieftain by his adopted brethren.

March 12, 1882: The Sunday Herald [Boston]: [Zuni]

The Zuni Indians.

Mr. Cushing Relates His Experience Among Them in New Mexico.

(Special Dispatch to the Herald)

[Copy of Evening Star March 11 story]

March 14, 1882: Evening Star: [Zuni]

The Zunis at Mt. Vernon.—Mr. Cushing and Mr. and Mrs. Stevenson took the party of Zuni Indians now visiting here on an excursion to Mt. Vernon and further down the river yesterday. This is the first visit of these Indians to Washington. They worship large bodies of water and were greatly impressed by the site of the Potomac, as they have no important rivers where they live, and they were performing their devotions throughout the trip.

March 15, 1882: Evening Star: [Zuni]

The venerable Zuni chief, now in this city, was very ill yesterday.

March 16, 1882: Daily Critic (DC): [Zuni]

The old Zuni Chief, now visiting the city, is quite ill, the result of his trip to Mr. Vernon on Monday [March 13]. The scene that day was really impressive, for the Indians, observing the width and quiet majesty of the Potomac, rose simultaneously, and, with many gestures and low reverences, muttered prayers and uplifted faces, began to worship it. Large bodies of water are among their gods; the clouds, great winds and sun sharing the adoration.

March 18, 1882: Evening Star: [Zuni]

The Zuni Indians at the White House.

The Zuni Indians, or the cliff dwellers of western New Mexico, called upon the President this afternoon, accompanied by Mr. Stevenson and Mr. Cushing. They know that General Washington is dead, but they believe that the President is his lineal descendant, and they were very desirous of seeing and touching him.

The President expressed to them through Mr. Cushing his pleasure at meeting them. They were introduced individually. Several of them made remarks, which were interpreted by Mr. Cushing. One said, “The days have now come when we take our father Washington by the warm hand. We look upon him and he looks upon us.” Another said, “May the light of God shine on you.”

March 20, 1882: Cleveland Leader: [Zuni]

The Zuni Delegation. Special Dispatch to the Leader.

Washington, March 18.—The Zuni Indians, or the cliff-dwellers of Western New Mexico, called upon the President this afternoon, accompanied by Mr. Stevenson and Mr. Cushing. They know that General Washington is dead, but they believe that the President is his lineal descendant, and they were very desirous of seeing and touching him. The President expressed to them, through Mr. Cushing, his pleasure at meeting them. They were introduced individually. Several made remarks, which were interpreted by Mr. Cushing. One said that “the days have now come when we take our father Washington by the warm hand. We look upon him, and he looks upon us.” Another said: “May the light of God shine on you.”

March 24, 1882: Caledonian [St. Johnsbury, Vt.]: [Zuni]

The Zuni Indians.

A Strange and Interesting People.

The Zuni Indians, a tribe on the western border of New Mexico, number about three thousand, are peaceable and kindly, and possess a unique ancient and considerably developed civilization. A delegation of them has just been in Washington on its way to Plymouth, Mass., under the guidance of Prof. W. H. Cushing, of the Smithsonian Institute, who has lived among them for several years, has been received as a member of the tribe, has been admitted to their secret orders, and has made a careful study of their history and customs. Prof. Cushing is about to be initiated into their most exalted mystery, with which is connected the use of water from the ocean. Their stock of this water being nearly exhausted in the many years since they have seen the ocean, and it being required that Prof. Cushing should marry a Zuni woman before being fully initiated into their secrets, he offered, instead of being married, to conduct a party of chiefs to the ocean for water, and his offer was accepted. So Plymouth is about to witness the strange rites of the tribe, and it is to be hoped that the interesting occurrence will not be interrupted by too inquisitive spectators.

March 29, 1882: Daily Critic (DC): [Sac and Fox]

The delegation of Sac and Fox Indians now in the city, under charge of Inspector Haworth, had a conference with Secretary Kirkwood this morning in reference to removing to the Indian Territory. The Indians were divided as to the propriety of removing, and another conference will be held to-morrow. Several of the Indians appeared in all the gorgeous of their native costumes.

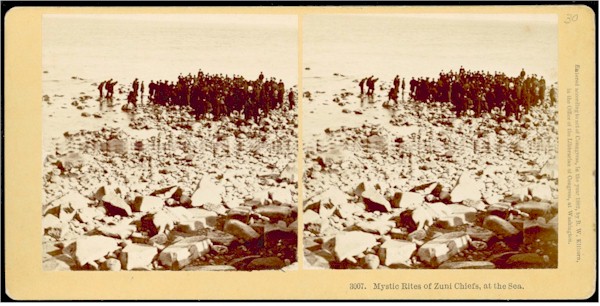

March 29, 1882: Boston Journal: [Zuni, Hopi]

The Zuni Indians.

Yesterday’s Pilgrimage to the Sea—Interesting Ceremonies and Unusual scenes at Deer Island.

The spectacle of a number of Indians uttering prayers and incantations to strange gods, and casting votive offerings upon the waves of the sea, as they chant the songs of their religion and celebrate mysterious rites, is not a common one on the shores of Massachusetts Bay in the present year of grace, however ordinary it may have been three hundred years ago. The occurrence of such an event would naturally have a profound effect upon the people of New England, who are notoriously frond of seeing a show, and so, when announcement was made in the newspapers that the band of Zunis now visiting the city was about to make a pilgrimage to the shore of the outer sea, everybody who could obtain an invitation to attend from the Mayor of the City Government, who had the matter in charge, made haste to do so. The result was that when the Zunis yesterday afternoon arrived at the steamer J. Putnam Bradlee, which had been placed at their disposal by the city of Boston, they found the vessel filled to nearly its utmost capacity by the curious pale-faces who had determined that their enterprise should be sanctioned by as agreeable a company as could be collected. Among those who tent their countenance to the occasion were Mayor Green and a majority of the Board of Aldermen, Rev. Phillins Brooks, Professors Putnam and Horsford of Cambridge and Morse of Salem, Collector Heard, and a number of others more or less distinguished. The Zunis were brought from the Quincy House to the Eastern avenue wharf in hacks, accompanied by Mr. Cushing and several other gentlemen. All were in their most splendid habiliments—that is to say, the Indians were—while Mr. Cushing appeared in the ordinary clothing of civilization, donning his savage costume only after the boat had nearly reached Deer Island, where the mystic ceremonies were to take place. The delegation was immediately taken to the pilot house, whither followed, in spite of the conspicuous notice, Positively No Admittance, so many of the passengers that the man at the wheel had hardly elbow-room. When the boat fairly got into the stream and the harbor broadened out in their view, the Indians, awe struck by the sight of so much water, began to mumble their prayers to the gods of the ocean and chant their sacred songs, anon scattering to the winds and waves pinches of consecrated meal, which is composed of ground shells and sand, mingled with powdered white corn—thus offering, as their religion teaches, the sea’s products to the sea itself, and also the grain, which is to them the symbol of terrestrial life by the subsistence. Mr. Cushing, the director of their wanderings in the strange land of the East, vainly attempted to convince them that the water upon which they then were was not the illimitable deep of which they had heard from the traditions preserved in their tribe, but they continued their prayers and scattering of meal for a considerable time, after which they looked upon the water and vessels about them with a quiet wonder which seemed too deep for expression. On approaching Deer Island, Mr. Cushing, who had withdrawn a short time previous, reappeared in his Indian dress and made preparations to take his charges on shore. The wharf reached, the Zunis were loaded into a van, a second was filled with ladies, and the male members of the company who could not hang on to the steps of these vehicles made the best of their way after them on foot to the eastern side of the island. The wind blew a half gale and was nipping and chill, but the sky was clear, the air invigorating, and the scene unusually beautiful. The tide, whose waves were smoothed down by the wind that blew off-shore, was rising gentle as the Zunis, followed by some two hundred spectators, including several enterprising photographers with field cameras, reached the two tents which had been pitched for them on the shore of the mysterious ocean of the sunrise. Into the larger of these structures the Zunis and Mr. Cushing retired to prepare themselves for the coming ceremonies. While waiting for them to reappear, some account of the occasion and meaning of the acts they are about to perform may be of interest. As near as could be learned in a hasty interview with Mr. Cushing—who, in spite of the demands made upon him, found time to give the newspaper men much interesting and singular information—the Zunis, like most Indians, look to the East as the source of all beneficent spiritual influences. The Eastern sea, or, as they speak of it, the ocean of the sunrise,” is regarded by them with especial reverence. From it come the summer and the summer rains, and its water is considered sacred because of the advantages which it is supposed to bestow upon the nations. A quantity of this water is always kept in the tribe, and used in the religious rites which are celebrated to bring the season of warmth and fruitful rains. The present supply of sea water now running low, a part of the purpose of the excursion of the Zunis to the East was to secure a new store of it, to do which efficaciously certain ceremonies and forms must be observed. When the last previous expedition to the Eastern sea occurred, or at what point the sacred water was procured, is unknown, it is thought, however, that at least three generations have passed away since such a pilgrimage was made, and several hundred years may elapse before the Zunis again appear on the shores of the Atlantic. This sacred water is kept closely sealed in hollow canes, which are held in the temples of the tribe, and is used very sparingly and only by the priests and chief men of the highest sacred orders.

When the chiefs and Mr. Cushing had completed their preparations in the tent, they emerged upon the sand and betook themselves with solemn steps to the shore, followed by the crowd, men, women and children, who slipped and stumbled over the wet rocks, and fell down and got up again in a manner wholly inappropriate to the solemnity of the occasion. A stranger procession never appeared hereabout. First came several policemen, who attempted to keep the crowd in order and shouted loudly to it all the time to “keep back—which the crowd, as usual, did not do. Then came Mr. Cushing, clad in a blue shirt of native cloth, buckskin leggings and moccasins, and decorated with silver buttons, crescents and buckles, strings of beads and shell bracelets. He also wore upon his head a bearskin cap, somewhat like the illustrations of Robinson Crusoe’s head-gear, which a number of feathers stuck into the side of it, and was agreeably decorated with a streak of black paint which ran under both eyes and across his nose, while a large spot of the same appeared on each cheek. The chiefs were dressed nearly as they have been on former occasions and similarly to Mr. Cushing, except that one wore gorgeous green breeches and had a skin skullcap on his head. While another had inexpressibles of a stuff resembling black plush. All were painted in the pleasing pattern above described in the case of Mr. Cushing, except that the color favored by one was red and by another yellow. The effect, however, was about the same, and in no case entirely pleasing. The Indians bore upon their backs their shields and weapons of war, and in their hands carried hollow gourds and glass vases, with which to take up the sacred water. After a protracted and irregular scramble over the rocks the delegation, followed by an irregular mob of sight-seers, reached a point where they could look eastward over the sea without any land appearing before them, and began their incantations. Squatting on their haunches on the weedy rocks, and with their vessels for holding the water placed upon the ground before them, they began a prayer chant in a subdued tone of voice, scattering meal from their pouches upon the seas as they did so in four different directions, to propitiate the gods of the north and the south, of the upper and lower regions, the “mother of the ocean and the father of the world.” The symbol of this strewn meal is of a road or path which the priests mark out with it signifying a request that the paths in life of the suppliants and their children may be “finished”—to use the Zuni expression—or drawn out and prolonged, as we should any in uttering the same idea. While this was going on, those members of the assembly who had arrived on the scene of action first crowded about the chiefs and watched their actions with an absorbed interest, which evidently made them unconscious of the cried of those less fortunate, who from behind loudly exhorted them to “get down in front.” The policemen, also, uttered stern commands from time to time for those in front “to fall back and form a ring,” but as the rising tide left only the top of a rock here and there exposed, and each person who had such a point of vantage clung to it for fear he should not get rest for the sole of his foot elsewhere, little was gained. As the sea rose a number of the more venturesome members of the assembly found themselves cut off from the shore, and were obliged to wade in to the beach, while an enterprising photographer, who had boldly planted himself on two small stones in the very front of the kneeling Zunis and trained his camera upon them, was soaked up to his knees before his negative was taken. The Indians, however, were much pleased with the rising tide, considering it, in their ignorance of physical geography, a mark of especial favor on the part of the gods of the sea, and, despite Mr. Cushing’s attempts to dissuade them from remaining, they persisted in completing their chant and the petition. They even looked upon their counselor with some disfavor, and urged him not to be faint hearted, but to remain and see the favorable purpose of the gods. Although seeing the sea on this occasion for the first time, they manifested not the slightest alarm, although evidently awestruck and impressed with the majesty and power of the waves.

Their position at last becoming untenable, the Chiefs removed from the rocks to the sandy beach further to the south, where the remainder of the ceremony was performed. Here the efforts of the policemen in their attempt to “make a ring” were more successful, and an irregular crescent of spectators was formed, about a hundred feet across, and with its tips resting near the water. Here everybody could see, and the Indians concluded their ceremonies without interruption. Sitting close together in a circle, they and Mr. Cushing smoked sacred cigarettes made of cane filled with tobacco, and as they smoked they prayed and blew the smoke among the feathers of the prayer-sticks they carried, after which they cast them into the waves. Then the two head Chiefs, taking off their moccasins and leggings, waded into the icy waters and filled their vases and gourds, after which they proceeded to the tent, followed by the others, of whom Mr. Cushing and one of the Indians whirled in the air sticks at the end of twisted thongs, by which a whizzing sound was produced and the gods informed that the ceremonies were ended. At the tent another song was chanted, in which the good expected from the services was recited, and meal four times scattered westward in the direction the chiefs must take in returning to their own land.

After a quarter of an hour thus passed the party again appeared and proceeded to the shore, bearing seven large demijohns in wooden cases, which they filled with water to take home with them. Arrived there this also will be dedicated in manner similar to that above described. Mr. Cushing’s initiation into the highest order of the Bow then followed. He was led to the edge of the shore, and there, deprived of his head-dress, he was baptized by having water poured upon his head and his hands washed. He was then embraced by all the chiefs—first by the first priest, then by his father by adoption, thirdly by the second chief, fourthly by his brother by adoption, and lastly by the Moqui member of the delegation, all pressing their hearts against his, and all praying that he might be made efficient as a priest of the Bow, and introducing him to the gods as brother and a firm relative. This ceremony takes Mr. Cushing into the highest order of the tribe and makes him in all particulars a Zuni. The ceremony of yesterday, however must be repeated on the return to the land of the tribe with many hard ordeals, among which is a fast of four days and nights. He will then be permitted to learn all the secret history of the tribe, which is expected to throw much light upon Indian history in America, and especially an epic account of its existence, which required twenty-six hours in the recital, and will demand, as Mr. Cushing things, four years of his time in learning it.

After this ceremony the Indians and the company proceeded to the reformatory building, where the boys and girls were awaiting them. Here a half hour was pleasantly passed in listening to music by the children, after which the Zuni gave a song, describing their journey and its object, which much edified and amused the youngsters. The crown then proceeded to the boat and returned to the city, where they arrived at about six o’clock. In the evening the Zunis and Mr. Cushing visited the Boston theatre and witnessed the performance of “The World.”

March 30, 1882: Evening Star: [Sac and Fox, Iowa]

A Satisfactory Indian Conference.—the delegation of Missouri Sacs, Iowas, and two Sac and Fox Indians from the Indian Territory, had a conference to-day with the Secretary of the Interior and Commissioner of Indian Affairs. They wanted to arrange about their land at the Great Nemaha agency, a part wanting to remain there and a part in the Indian Territory. After a considerable talk, the conclusion was reached that the Indians must go back to the Nemaha agency, and from there send a delegation to look at the country below. If they found a country to suit them then they could report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. This arrangement was satisfactory to the Indians. They will start for their home in a few days, stopping on their way at Carlisle to see their children.

March 30, 1882: Boston Herald: [Sac and Fox, Iowa]

The Sac, Fox and Iowa Indian delegation had a conference with the secretary of the interior and the commissioner of Indian affairs today, concerning the proposed consolidation of these tribes on one reservation in the Indian territory.

March 31, 1882: Owosso Times [Owosso, Mich.]: [Zuni]

The Zuni Indian delegation were on Tuesday conducted by Boston officials to the brink of the ocean, where they chanted songs and scattered the sacred flour which they brought from New Mexico.

March 31, 1882: Boston Herald: [unid.]

Visiting Indians Plied with Liquor.

Washington…..

Officials of the Indian bureau state that several members of the Indian delegation now in this city have been enticed into liquor saloons and plied with liquor. Sec 2139 of the Revised Statutes especially forbids the sale of intoxicating drinks to Indians under heavy penalties, and it is the intention of the Indian bureau to prosecute the dealers who have been guilty of selling them liquor under this section.

March 31, 1882: Cincinnati Commercial Tribune: [Sac & Fox, Iowa]

Indian Conference

The Sac, Fox and Iowa Indian delegation, after an interview with Secretary Kirkwood, desired to send a delegation to the Indian Territory to agree upon suitable land there, and to report to the tribes for their decision.

[This story is carried by several newspapers; not copied]

March 31, 1882: Philadelphia Inquirer: [Sac & Fox, Iowa]

Indian Conference.

The Sac, Fox and Iowa Delegation Heard.

Washington,--March 30.—Secretary Kirkwood had another conference to-day with the Sac, Fox and Iowa Indian delegation at the Interior Department. These Indians have come here at their own expense to consult with the Secretary as to the advisability of removing from their present reservation in Nebraska and settling on lands in the Indian Territory. The Indians finally decided to go home and send a delegation to the Indian Territory to agree upon suitable land there and report to the tribes for their decision.

Officials of the Indian Bureau state that several members of the Indian delegation now in this city have been enticed into liquor saloons and plied with liquor. Section 2139 of the Revised Statutes especially forbids the sale of intoxicating drinks to Indians under heavy penalties, and it is the intention of the Indian Bureau to prosecute the dealers who have been guilty of selling them liquor under this section.

April 3, 1882: Truth [New York, NY]: [Zuni, Hopi]

The Sun Worshippers.

A Sabbath Séance With The Zuni Indians.

Brooklyn’s Boys Interested—the Priests and War Chiefs of the Tribe—A White Medicine Man—the Twofold object of their Tour—On Their Reservation

Truth spent a Sabbath morning yesterday among the Zuni Indians. They were at the temporary residence of Mr. Frank H. Cushing’s parents, No. 49 Joralemon street, Brooklyn.

As Truth rang the door bell he became the cynosure of all eyes—that is, all those certain eyes belonging to the juvenile parties across the street. The children of the vicinity appeared to have turned out en masse, to the great neglect of their religious duties. If there is any one particular thing in the wide world which fills a city urchin to the brim with curiosity it is the sight of a wild Indian, and five of them at once totally demoralized the youthful denizens of Brooklyn’s western slope.

They were there when Truth called, and were standing guard by reliefs all day. They had got the sacred songs of the Zunis, which floated out through the second story windows, “down fine”—to their own satisfaction, at least. But when they began to cultivate their vocal talent for war whoops, by emitting prolonged and dismal yells, at the same time patting their mouths with their hands, it aroused the neighbors, annoyed Mr. Cushing, and visibly excited the otherwise pacifically inclined aborigines.

The Zuni Tribe.

It should be premised that Mr. Cushing, who is about 24 years of age, was deputized to visit the Zunis by Professor Baird and Major Powell of the Smithsonian Institute, for the scientific purpose, in plain words, of studying their language, traditions, religion and customs. The importance of this trust will be appreciated when it is known that the Zunis are the modern representatives of the old sun worshipping tribes. They combine the features of the Aztecs and Incas of Peru, resembling more nearly, however, the latter. They are in no way recently related to the Aztecs, however. Their reservation is in New Mexico. Mr. Cushing is a member of the tribe, and will appear in the category of the present delegation according to his proper rank.

Personnel of the Delegation.

Lai-iu-ah-tsai-lun-kia, second high priest or cacique of the nation. He bears a somewhat remarkable facial resemblance to Dante, the Florentine poet. He is Mr. Cushing’s father by clan adoption Mr. Cushing’s natural father is, consequently, although a recent acquaintance of the second encique’s, regarded by him with fraternal affection.

Nai-in-tchi (the woman’s wonderful_ first priest of the “Order of the Bow,” and first priest or encique of war.

Ki-a-si-wu, a second priest of the “Order of the Bow,” and second priest or encique of war.

Te-na-tsa-ti (medicine flower), Frank H. Cushing, head war chief, third priest of the “Order of the Bow” and second head chief of the nation.

Pa-lo-wah-ti-wa (the burier), head peace chief of the tribe and warrior chief of the “Order of the Little Fire” (Mr. Cushing’s brother by clan adoption and by blood friendship.

Na-na-he (soot flower of corn) Moqui Pueblo Indian, adopted into the tribe, having married a Zuni maiden.

The dusky braves were grouped upon the floor about the rooms. Their faces were “wrinkled and brown like a bag of leather,”” as the countenance of the old squaw of the Sierras was poetically depicted by Joaquin Miller. They smoked cigarettes constantly, which they rolled themselves. Their knife-sheaths flapped empty from their sashes, and the atmosphere that surrounded redskin and paleface was redolent with the fumes of tobacco, and suggestive of hatchets buried too deeply to be ever dug up. Several ladies and children were in the room. The latter regarded the Indians with curiosity, not unmixed with fear at first.

The Picturesque Moqui.

The dress of the natives was picturesque. The Moqui is the youngest, and is the Beau Brummel of the delegation. His raven locks were parted in three, the largest shock behind. It was twisted and doubled up in a clumsy bunch and secured with a parti-colored ribbon and a collection of hairpins, which are souvenirs of Platonic friendships with the Boston girls, about which he will probably prevaricate to Mrs. Na-na-he upon his return to the family wigwam. The side locks were restrained from falling over eyes and cheeks by gaudy bandana handkerchief bound around the temples.

Around his neck he wore several strands of beads, white and blue. At his throat was a large shell. Its pearly lining bore a conventional landscape [illeg.] hand painted.

Truth reflected that the fair donor would not find the vicinity of the Na-na-he campfire conducive to longevity.

A navy blue flannel shirt (very decollete corsage), with the sleeves ripped at the under seams to allow greater freedom; a red flannel undershirt; black velveteen breeches, with silver buttons down the outer seams; leggings of dressed buckskins, secured with red tape garters and plain moccasins which encased his pedal extremities, completed his gaudy costume.

An Unexpected Linguist

During Truth’s visit a lady called, who informed Mr. Cushing that she had lived near the Zuni reservation from 1867 to 1870, her husband, a United States Army officer, having been stationed at Fort Wingate and other posts still nearer. The Indians were first astonished, and then visibly delighted, when their visitor addressed them in their native tongue.

The object of the Zunis’ long journey was to obtain sea water from a point nearest the rising sun to mix the paints for their prayer sticks. This has long been an ambition of the tribe, and their white brother availed himself of the opportunity to assist them, and further the cause of science by accompanying them. One of the Zunis and the Moqui will remain in Washington for a time with Mr. Cushing; the others will return with his brother. With the assistance of the Moqui, the collection of the Moqui implements and utensils in the Smithsonian Institute will be classified.

The Zuni reservation is in Valencia County in the extreme western part of New Mexico. It is thirty-five miles south from the nearest point on the Atlantic and Pacific extension of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, that point being [thirty?] miles south of Fort Wingate. It is fortunate for these interesting people that their land is not rich in ores,, and is therefore not likely to tempt the white man’s cupidity.

The characteristic of this tribe, which numbers some 1,600 souls, are in the main creditable. They have never stolen horses nor killed white men.

While the delegation was at Salem, Mass., one of the priests addressed an audience through Mr. Cushing’s interpretation, and said that among other things he had learned that they formerly burned witches there. He added that he hoped they would have strength of mind enough to kill them, as their fathers had before them.

[story about witch on the reservation; general info. on the Zuni agency = edited out here]

Mr. Cushing said that the life of the Zunis was almost a pastoral poem. It is not to be inferred from this, however, that their domestic habits and cuisine are not often repulsive to the conventional ideas of civilized man. They sang several of their sacred songs. A sacred call was liberally translated as follows:

An Aboriginal Hunter’s Chorus.

“Ye who watch over the order of the hunt, I call upon you this day, I ask you to look before and behind, and see that all is well. Go forth, my children, over the fields, the old and the new. Cast your thoughts and eyes before, behind, and aslant. Think always upon the gods, upon those who gaze with smiling faces upon you. Go forth and labor and return, always with prayer in your hearts. Thus haste ye over the road to the hunt.”

April 6, 1882: Bennington Banner [Bennington, Vt.]: [Zuni]

[Copy of March 29, Boston Journal article]

April 7, 1882: Evening Star: [Zuni]

The Zuni Indians in the city had a reception last evening at No. 1374 B* street southwest,

which was largely attended. [*James and Matilda Stevenson lived at 1405 H Street in 1882, so not their house]

April 8, 1882: Evening Star: [Zuni]

About the Zuni Chief.

What He Does and Says—Why the Zunis Admire Water—The Chief Visits the Government Printing Office—He circulates in Society.

The aged Zuni chief, Pedro Pino, is still the guest of Prof. and Mrs. Stevenson. He constantly expresses himself as very happy and contented there. He is very observant and is quick to learn the habits approved by those about him. He never smokes without having a spittoon between his feet, and invariably uses it when expectorating, and if he chances to be in a room where there is none, goes in search of one when he has need of it. He has also learned to use a handkerchief and keeps one always about him ready for use. He made a visit lately to the Government Printing Office, which greatly delighted him, and he gives graphic descriptions in words, as well as by unmistakeable gestures, of what he saw there and how so many women sewed paper together to make books, and of what he saw others doing. He denies that the other Zunis went to Boston to perform religious rites at the ocean. He says they wanted to get shells, but did not come so far only for that purpose. Those who know their customs and beliefs thoroughly say that the Zunis always go through with religious ceremonies when they see a body of water, even the ponds and little creeks which they have in their own country. They pray that the water may rise to the skies in clouds and descend in rain upon Zuni to make their crops grow. They s often need rain in their country that they naturally look upon water as a source of life. They are, however, worshipers of the sun. They will take water from the Potomac back with them as well as water from the Atlantic. They had never before seen any large bodies of water, and it is the size they respect, because they think it can make more rain than small streams.

Pedro Pino is the greatest man the Zunis have ever produced, and has been for years favorably known, both to Americans and Mexicans who have gone to Arizona and New Mexico. He has held every place of honor among his own people, and although not now holding any office on account of his age, he is always consulted about every affair of importance. He has been highly delighted with the attention shown him here, as many ladies and gentlemen of high position have called upon him, and he has often been invited to spend the evening with others. Senator Logan’s daughter, Mrs. Tucker, gave him a silver bangle, which he wears constantly.

Lately he spent an evening with Representatives Carlisle, tucker and Willis and their wives and some of their friends, and was greatly pleased with Miss Gertie Tucker’s singing and with the dancing of some of the young girls present, who danced especially for his benefit. Pedro also sings when urged to do so a very pretty little Spanish legend about Montezume and Saint Guadalupe. He has a very sweet, clear voice for so old a person.

He has never seen the style of dancing in vogue here before, and was greatly pleased with the motion of the feet, and said that Americans knew how to use their feet wonderfully. He is daily more impressed with the general knowledge of the Americans and constantly expresses his conviction that they know everything

April 10, 1882: Evening Star: [Zuni]

The Zuni Chiefs, now in the city, excepting one and perhaps two, will leave for Carlisle to-morrow or Wednesday, in charge of Mr. Bushing’s brother. The one or two who remain will assist Mr. Cushing in preparing his reports for the Smithsonian Institution.

April 12, 1882: Daily Critic (DC): [unid.]

A delegation of Indians were before the House Indian Committee to-day in the interest of a private claim.

May 13, 1882: Evening Star: [Caddo]

The Caddo Indian Delegation from Indian territory, who have been east for some months, returned to this city from Carlisle to-day. They wished to see the Secretary before leaving for home, and arranged for an interview on Monday [May 15].

May 23, 1882: Evening Star: [Caddo]

The Caddo Indians.—The Secretary of the Interior to-day directed the Caddo Indians to return to their homes. They have been here about two months.

May 24, 1882: Cleveland Leader: [Caddo]

Secretary Teller informed the Caddo Indian delegation, before starting for home, that he would do all in his power to protect their interests.

May 24, 1882: New York Tribune: [Caddo]

Washington, Tuesday, May 23…

The Caddo Indian delegation left this city to-day for their homes in the Indian Territory. They had a final conference before leaving with Secretary Teller, who promised to do all that lay in his power to protect their interests.

May 27, 1882: Salt Lake Tribune: [Caddo]

Washington, Notes. Secretary Teller informed the Caddo Indian delegation, on starting home, that he would do all in his power to protect their interests.

June 1, 1882: Eaton Democrat [Eaton, Ohio]: [unid.]

The Secretary of the Interior has been compelled to order several Indian delegations home from Washington, who were lingering about without knowing exactly what they wanted.

Aug. 2, 1882: Evening Star: [Cherokee]

Senate Proceedings.

The consideration of the sundry civil bill was resumed. The provision that the expenses, in Washington, of the delegation of Cherokees who visited the city last spring shall be paid out of any funds belonging to the tribe, as recommended by the Senate committee, was objected to by Mr. Voorhees. After debate the provision was modified to allow the money to be paid from the Treasury instead of from the tribal funds.

Dec. 6, 1882: Grand Forks Daily Herald: [Chippewa]

…We arrived on Sunday just in time to meet the breeds and Indians on their way to church, dressed in their Sunday best. There was a multitude of them. We met the chiefs Little Bull, Little Shell, Red Dog, etc., on their way to divine worship. They informed us that they intended starting for Washington the following morning, for a medicine talk, and felt quite elated. They are of the Chippewa band and think to own the country…

Dec. 13, 1882: Daily Illinois State Register: [Chippewa]

A delegation representing the Chippewa band of Turtle Mountain Indians, from Northern Dakota, have arrived at Washington, seeking a redress of grievances. Little Shell, chief, says that the lands and property of the Indians have been trespassesd upon and appropriated. They have appealed to the interior department for protection without success, and, as he says, without even securing attention to the subject. Little Shell says the trespassers are men from Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota, and that if they are not protected in their rights and property they threaten to take the case into their own hands, and will not answer for the consequences.

Dec. 13, 1882: Cleveland Leader: [Chippewa]

The Chippewa Protest.

A small band of Chippewa Indians arrived to-day from Turtle Mountain country, Northern Dakota. They came without the sanction of the Indian office, and to protest against opening to settlement of a large area of country to the north and west of Devil’s Lake, as contemplated by the recent decision of Secretary Teller. The Secretary holds that these Indians have no title whatever to the country. He finds that in all the published accounts of the Northwest Territory, even in writings of Jesuit missionaries two or three hundred years ago, the country is referred to as belonging to the Sioux. The visitors had an interview with the commissioner of Indian Affairs to-day. Bishop Whipple, it is understood, favors the claims of the Indians.

Dec. 14, 1882: Evening Star: [Chippewa]

The Chippewa Indians.—The delegation of Turtle Mountain Chippewa Indians, six in number, who have been in Washington for the past few days, had a short interview with Secretary Teller at the Interior department this afternoon. The Indians said the object of their visit to Washington was to ascertain whether they had any right to the lands now occupied by them in northern Dakota, and if not, whether the government would set apart a reservation for their occupancy. Secretary Teller briefly informed them that their right and title to the lands in question had been extinguished by treaty stipulations, but that he had already recommended to Congress that a new reservation sufficient for their needs be allotted to them, and that he had no doubt Congress would soon take favorable action in the matter.

Dec. 15, 1882: Philadelphia Inquirer: [Chippewa]

This afternoon Secretary Teller gave a hearing to the Chippewa Indian delegation. They claimed that the recent decision of the Secretary in the Turtle Mountain case did them great injustice. The Secretary refused to reverse his ruling.

Dec. 17, 1882: Boston Herald: [Chippewa]

The Chippewa Indian delegation had another conference with the secretary of the interior this afternoon. The secretary promised the Indians that he would set apart, by executive orders, for their use, a section of the former Turtle Mountain reservation in Dakota. He also notified them that he would send a representative of the department to their homes in the spring to look into their condition. The Indians expressed themselves as deeply grateful, and promised to send their children to school and go to work at farming. The delegation will probably leave here for their homes on Monday next. [Dec. 18 or 25]

Dec. 22, 1882: Evening Star: [Dakota: Oglala]

Washington News and Gossip

Red cloud, the notorious Sioux chief, who left the Pine ridge agency, Dakota, several days ago, is expected to reach the city to-night, arriving at the Baltimore and Ohio depot about 9:30 p.m. He will be accompanied by a single companion—a half-breed Indian interpreter.

Dec. 23, 1882: Evening Star: [Dakota: Oglala]

Red Cloud, who arrived in the city last night, called at the Interior department firs forenoon and paid his respects to Secretary Teller and Commissioner Price. He informed Secretary Teller that he would call again early next week and explain to him the object of his visit to Washington.

Dec. 26, 1882: Evening Star: [Dakota: Oglala]

Red Cloud called at the Interior Department to-day and had a few moments private conversation with Commissioner Price. What passed between them is as yet unknown to everybody excepting Red Cloud, the commissioner, and the interpreter. Red Cloud will leave Washington this evening to be absent several days on a visit to the Indian schools at Carlisle, Pa., and Hampton, Va. He expects to interview Secretary Teller soon after he returns to Washington.