CHICHESTER CATHEDRAL'S SPIRE:

Now You See It; Now You Don’t

Stereoscopic Snippets: Diving Down Rabbit Holes of Research

by Paula Fleming

Stereo World, November/December Vol. 46 #3

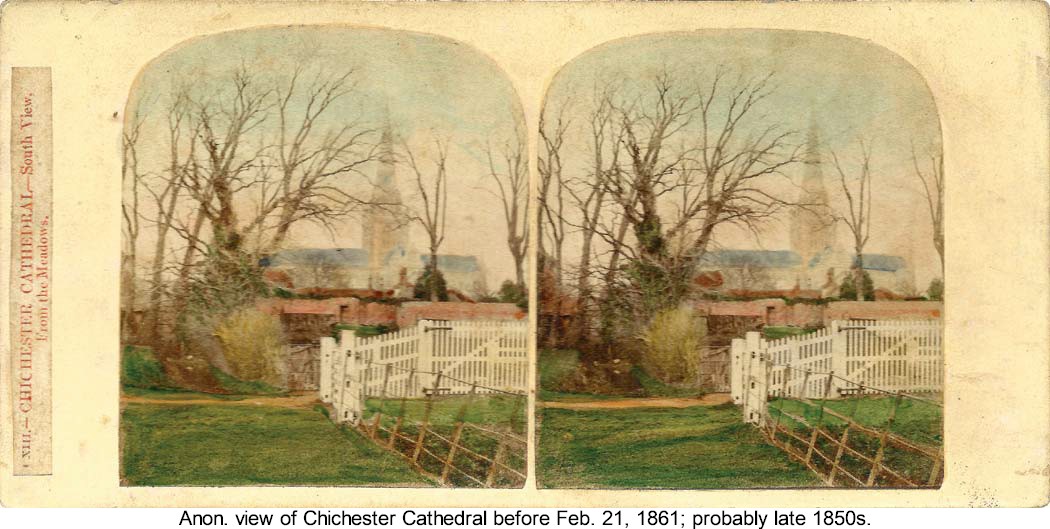

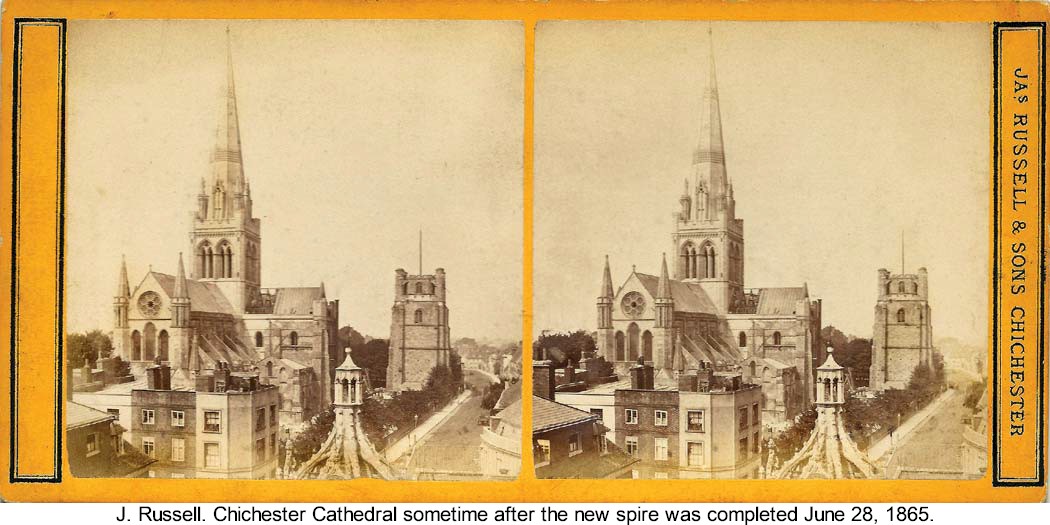

Chichester cathedral is located in West Sussex on the South coast of England. The spire is 272 feet tall, and is the third tallest in the UK after Salisbury (404 feet) and Norwich (315 feet) cathedrals. It is the only cathedral spire that can be seen from the sea and has served as a landmark to both pilgrims visiting the shrine and mariners entering the waters of the naval stronghold of Portsmouth harbor only a few miles to the West.

Chichester is an ancient city, built upon by a succession of cultures including the Romans who erected Fishbourne Palace about thirty years after they conquered Britain. The cathedral itself is equally ancient. In 681 St. Wilfrid founded a monastery in Selsey on land donated by the first Christian Anglo Saxon King Æoelwealh. In 1076 following the Norman Conquest the religious center was transferred ten miles inland to Chichester. There Bishop Odo of Bayeux, William the Conquerer’s half-brother, started construction on the cathedral. It was completed by Bishop Ralph Luffa and consecrated in 1108. As with many medieval buildings, the cathedral had its share of disasters. In 1114 and again in 1187 fires destroyed the roof. After repairs the building was re-consecrated again in 1199. The cathedral was made even more splendid in 1400 when a spire, cloisters and bell tower were built. Things went along smoothly until the outbreak of the English civil War in 1642 when Parliamentary forces ransacked the cathedral. Repairs unfortunately had to wait until 1660 with the restoration of the monarchy. Christopher Wren not only repaired the spire in 1684 but invented an interior structure that would counteract the force of the high off-shore winds. His inspired idea was to suspend a giant wooden pendulum inside, which worked perfectly. While Wren’s spire was protected from gales, it was still vulnerable to lightening which damaged it again in 1721.

For all their timelessness, even stone buildings need continual, expensive upkeep, especially those that are hundreds of years old. After suffering many years of neglect, Dean George Chandler started restorations on the cathedral in the 1840s, but he passed away before the work was finished. His successor, Dean Walter Farquar Hook, continued his restoration program, but took things one step further. In the fall of 1859, as a memorial to the late Dean, he decided on an “open concept” for the nave. His desire was to remove the fittings of the choir where the Divine service is performed, and as much as possible make it available for the use of the congregation. Accordingly the rood screen (which separated the chancel from the main body of the church), pews, pulpit, wood floors, stalls and the organ gallery were removed. All was going along nicely until early 1861. The removal of the fittings revealed serious defects in the supports of the great western arch. This was one of four arches on piers which were erected at the end of the twelfth century. These piers bore the enormous weight of both the tower and the spire, and had been subjected to settlements and displacements over the years. Further serious cracks started to appear in the south-west pier supporting these structures. On Feb. 14 the cracks began to enlarge. After service on the 17th, the nave was screened off and men worked night and day adding scaffolding, braces and supports. The eminent civil engineer, Mr. Alfred Thomas Yarrow, inspected the structure and reported that the cracks were only in the stone casings and not the piers themselves.

Not to worry! Popular opinion, however, took a dissenting position: The spire was going to collapse! Hoping to put an end to public panic the Brighton Gazette (among other newspapers) published a “Chicken Little” notice on Feb. 21, 1861. Noting that repair work was being done to avoid a dangerous situation, the Editor added, “We mention this solely because absurd reports have been and still continue to be circulated as to the danger of the spire falling, not only among street gossips, but among others whom we shall not have supposed to have believed every hearsay. We may add, for the comfort of those desponding individuals, that during last week the place was inspected by an eminent civil engineer, Mr. Alfred Thomas [correctly “Thomas Alfred Yarrow”]… Our news is only hearsay, but it is on well-founded grounds, or we should not publish it.” The West Sussex Gazette supported the Brighton Gazette’s position noting that even the new organist, a Mr. Aimes, would be playing the organ in three days for services, which would have been on Feb. 24th. Nothing to fear. At 1:20 p.m. on Feb. 21st while people were reading the Gazette’s “calming” notice, the cathedral’s spire sided with popular opinion and collapsed. What the Gazette didn’t know was workers had realized the core of the pier was indeed rotten which had to be dealt with immediately.

As the Illustrated London News explained:

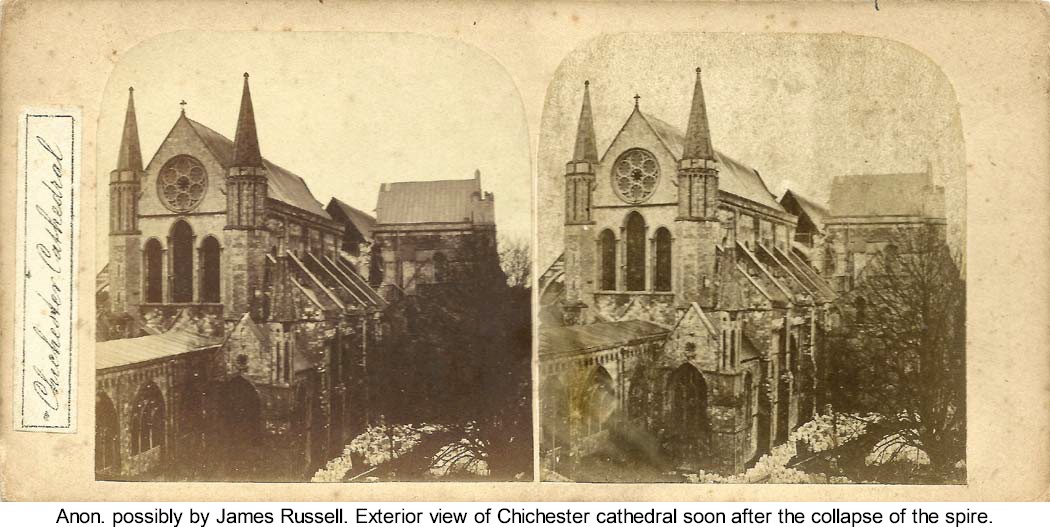

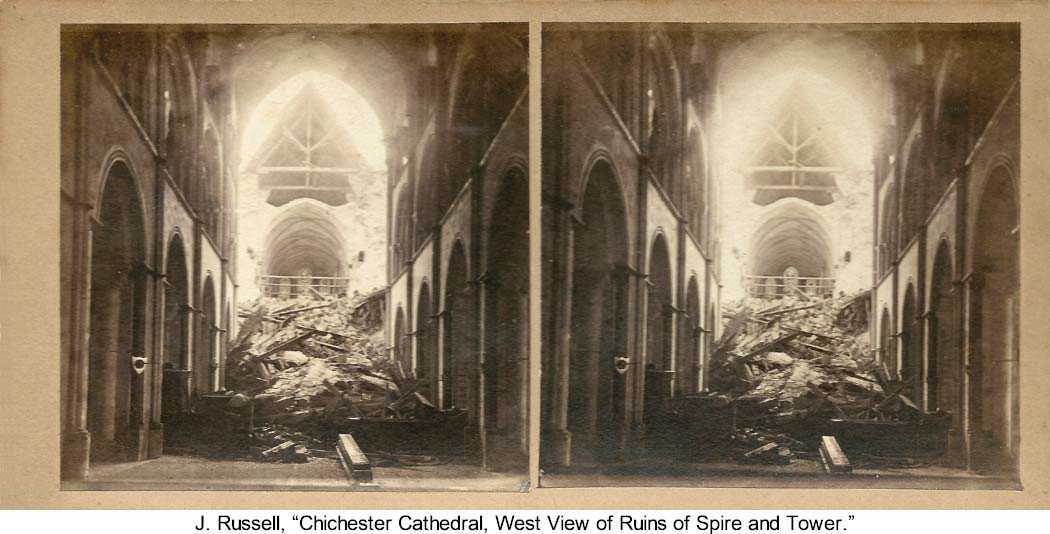

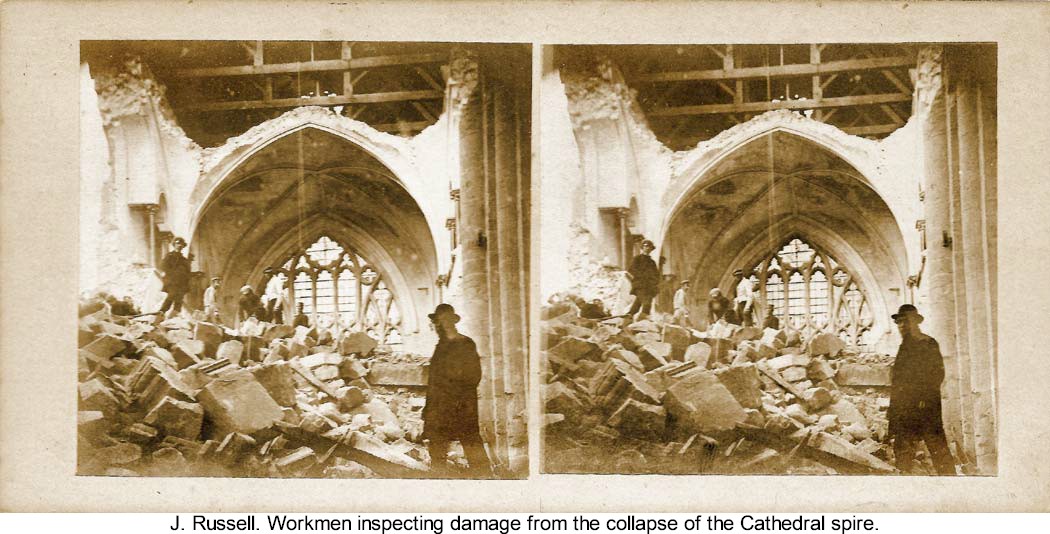

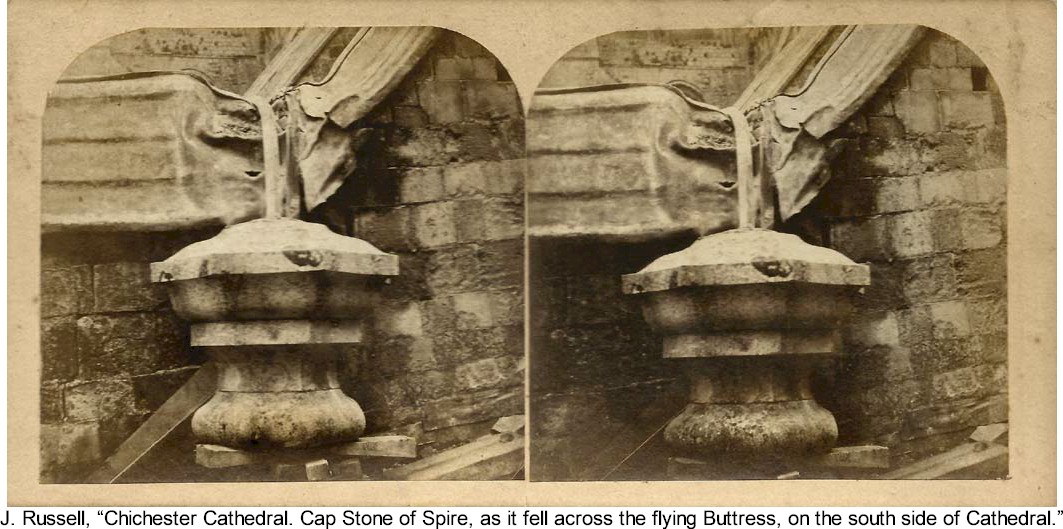

"The task of sustaining on each pier a weight exceeding 1400 tons thrust forward the facing on every side, and when the masonry was restrained in one place by props and shores the restraint caused it to bulge on the adjoining surfaces faster than it was possible to apply remedies. The terrific storm of wind on Feb. 20th caused difficulties to increase with alarming rapidity [perhaps Wren’s huge pendulum swinging inside contributed to the problems]; but the efforts of the sixty workmen appeared still to offer some possibility of ultimate success when, at three hours and a half past midnight, they quitted the building. Three hours later when they returned it was obvious the situation was getting worse. The immense pressures at work had caused the separation of the church walls from the supports of the tower, heavy stones burst out and fell, the core of the south-west pier poured out, crushed to powder, and the workmen were cleared out of the building while the noble spire was left to its fate. Not more than a quarter of an hour later the tower and spire fell to the floor with but little noise, forming a mass of near 6,000 tons of ruin in the center of the church, and carrying with it about 20 feet in length of one end of the nave, and the same of the transepts and choir. The fall of the spire was compared to that of a large ship quietly but rapidly foundering at sea. 1

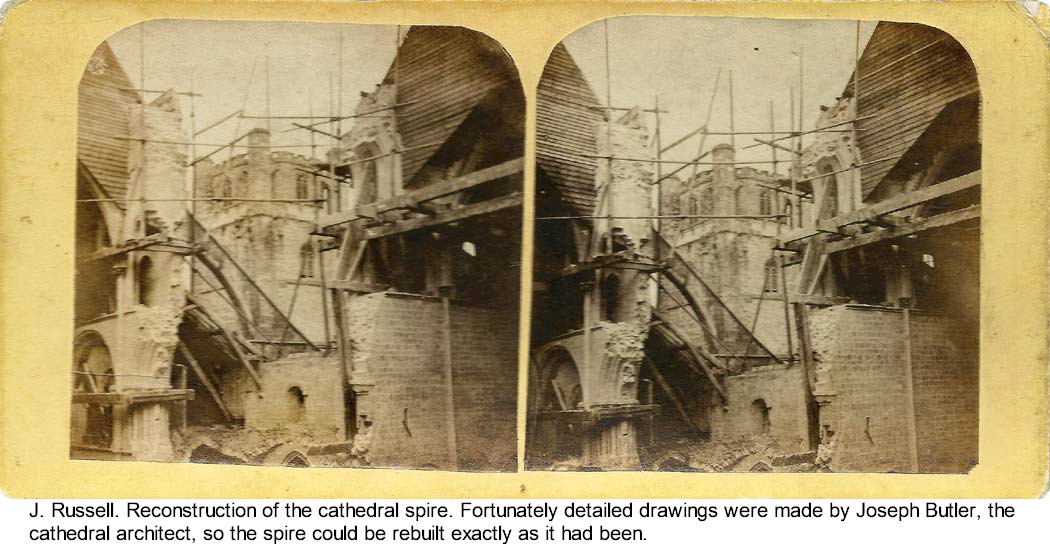

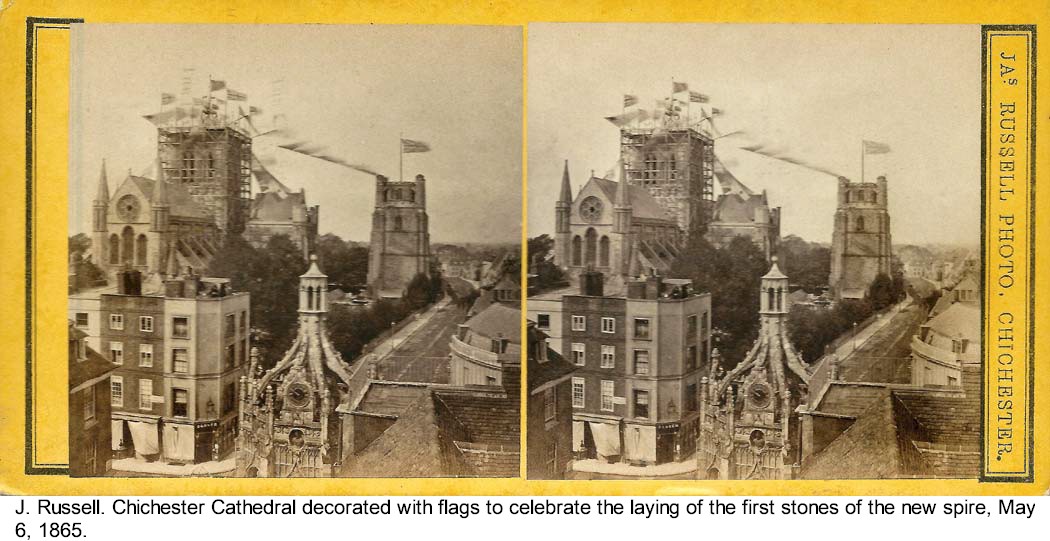

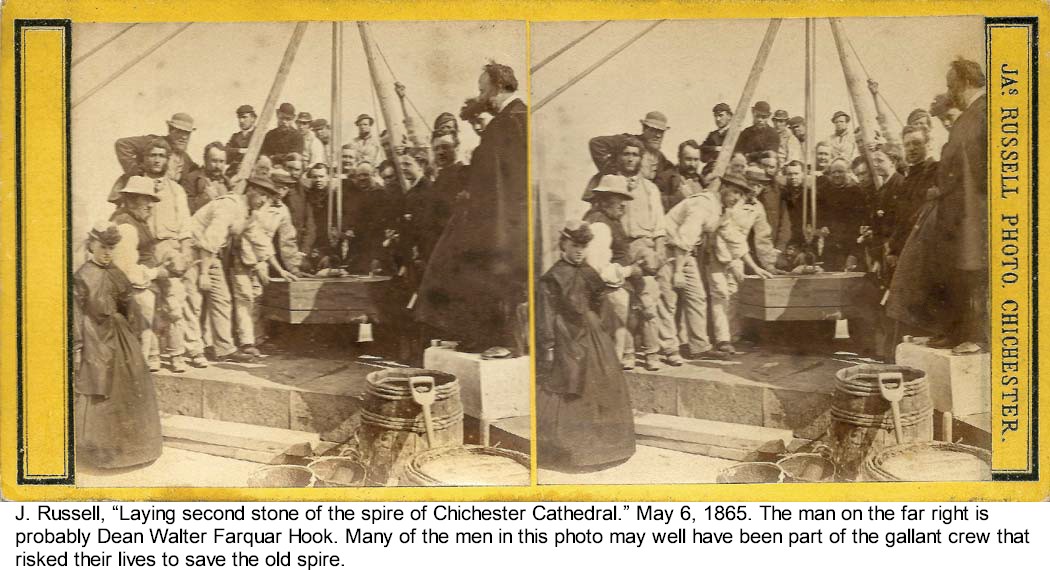

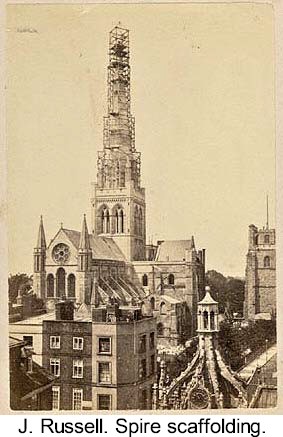

Fortunately no one was hurt, and miraculously the major shrines, etc. were unharmed. Also fortunately Joseph Butler, the cathedral’s own architect, and his son, William, had made very detailed drawings of the cathedral so reconstruction of the spire in its original form could take place. It should be noted that Butler warned that the spire was going to fall, but officials did not heed his informed opinion. The site was cleared of debris, and funds were acquired. On May 6, 1865, the tower gaily decorated with flags, the first stone of the new spire was laid with great ceremony. Finally on June 28, 1866, the spire was completed and the church reopened. These events were all documented by Chichester photographer James Russell. Originally a pawnbroker and then a master cabinet maker, he was forced to declare bankruptcy on Sept. 29, 1854. On Nov. 9th his entire cabinetry business and workshops were put up for sale to satisfy his creditors. Like the cathedral’s spire, his career had crumbled around him. Also like the spire, he arose from the disaster and bounced back, establishing a photographic business. Although he claimed his firm was established in 1853, the first listing for him as a photographer is in the 1858 Directory of Sussex with data gathered the previous year, thus 1857. Probably he was taking photographs as a sideline to his carpentry business, but no proof has been found to support the early date. His photographic business was a great success. His family, notably his sons James and Hezekiah, joined the business which ran for forty-six years in Chichester, finally closing in 1903. The company also opened branches in other cities including London where they photographed royal sitters, and were given a Royal Warrant on May 3, 18972 2.

I suspect the day the Chichester cathedral spire fell was a turning point in Russell’s life. He certainly took full advantage photographically of the situation. No doubt these images helped his rather young business. Yarrow, the civil engineer who declared the spire was safe, retired later that year due to “ unremitting attention and anxiety” 3.

Aimes, the organist whose life could have ended at the keyboard, finally got to play for services. But I can’t imagine the Editor of the Brighton Gazette ever lived down his editorial. As for the cathedral, there was an old local proverb which said, “If Chichester church steeple fall; In England there’s no king at all”. The proverb was proven to be correct since the spire fell during the reign of Queen Victoria.

Notes

1. Illustrated London News, March 2, 1861

2. photohistory-sussex.co.uk/RussellJasGallery.htm

3. Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers,

vol. 39, 1875, pp. 282-283. Obituary, Thomas Alfred Yarrow (1817-1874).