THE SIOUX

REVOLT OF 1862

or The Minnesota Uprising

by Paula Fleming

" 'A Portion Of The Promises Made To Us Have Not Been Fulfilled': Little Crow and The Sioux Revolt" in Native Nations: Journeys In American Photography, Jane Alison (Ed.) Barbican Art Gallery, 1998

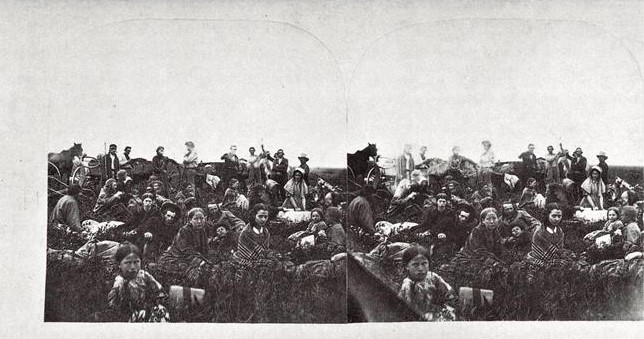

PLATE 136 ADRIAN J EBELL

White people escaping from the Riggs and Williamson missions near the

upper agency, during the Sioux Revolt of 1862.

Albumen stereograph. National Anthropological Archives,

Smithsonian Institution

A PORTION OF THE

PROMISES MADE TO US HAVE NOT BEEN FULFILLED':

LITTLE CROW AND THE SIOUX REVOLT

PAULA RICHARDSON FLEMING

THE STUDY AND RESTUDY OF VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHY has developed rapidly in the last thirty years. Once photographs were viewed as 'never lying' and 'worth a thousand words'. When researchers realised that photographs were useful as historical resources, the first task was to make sure that the basic questions of 'who? what? where? and when?' were correctly answered before the 'why?' could be attempted.

Scholars have now engaged photographs on new levels, answering some of the 'whys?' and demonstrating that the photographers and sometimes the subjects themselves are factors in framing the photographic story that is presented to the viewer, whose own background and reactions are also relevant. Postmodernistic interpretations of photography have thus provided insights into images and opened up new avenues of discourse, but as with any trend we must step back and see where we are going as well as where we have been.

Obviously we can no longer view the camera as an impartial truth' unit that provides an unbiased view of the world. Our eyes have been opened, but we must guard against getting carried away with our newly found understanding and losing sight of the basics. Our viewpoint can become so distant that we are in danger of not being able to see the proverbial wood for the trees. We must make the photographs live again by remembering the basic stories surrounding their creation. Photographs documenting the tragedies of war are highly emotive windows. Today we can visualise incidents in other parts of the world by turning on the TV, or reading photographically illustrated reports, but in the 1800s, newspapers and magazines were illustrated only with line drawings, if at all. Photographs, especially stereographs (the 'virtual reality of the day), provided the mode by which people put faces on stories they read. No doubt each viewer reacted differently and as for the photographer, other than a profit motive, we probably cannot document what compelled them to make their portraits. Ultimately, many of these images acquired an exotic appeal and were used for anthropological purposes but their original creation was most likely as a photo journalistic endeavour providing a focus for stories in the news.

As a case in point, I offer a series of photographs taken mainly in 1862 and 1863. These photographs are not outstandingly artistic, they are faded, and not very eyecatching, yet they document a series of incidents on the plains that killed more people than the Custer Battle and Wounded Knee combined. Nearly five hundred whites, mostly settlers, would be killed, and hundreds more taken hostage. Twenty-three counties in Minnesota would be virtually depopulated and nearly six thousand Native American Indians living on reservations would either flee the area, be imprisoned, or executed. Yet very few people have ever heard of the Sioux Revolt, or as it is sometimes called, the Minnesota Uprising.

My journey is to make these images live again by using the words of the original participants as much as possible to tell the events surrounding this. It is an emotional journey, yet it is not an apology for wrongs done to either side. Rather it is written with the hope that we will not get overly involved in interpretation and lose sight of historical context.

In 1858 Little Crow (pl.52), Sha-kpe' (also known as Six) (pl.53, 97) and other delegates from the Upper and Lower Sioux tribes, came to Washington, DC at the request of the US government to further discuss their land and to negotiate yet one more treaty with regards to their territory and annuities. This was the fourth meeting dealing with the matter and Little Crow had been involved in many of the negotiations. By the Treaty of 1837, the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux (1851) and the Treaty of Mendota (1851) the Dakota Sioux peoples relinquished claims to nearly twenty-four million acres of land, agreeing to live on a narrow strip of fertile land on both sides of the Minnesota River twenty miles wide. In 1854 Little Crow had come to Washington to deal with unclear title aspects and to discuss provisions that had never been fulfilled.

The issues were simple enough, but when caught in governmental red tape, successive administrations, an inability or lack of desire to deliver on promises made, and by all appearances negotiation in bad faith, the situation put two cultures on a collision course.

By 1858 half of the original agreement from the earlier treaties had been carried out - the North American Indian's land was gone; transferred to the US government, but most of the provisions and money had not been received in payment. Delegations from both the Upper and Lower Sioux came to the capital with the hopes of finally getting their due, while the government, wanted to negotiate for even more land. Thus Little Crow, Sha-kpe' and others had to negotiate one more time with the United States in an attempt to save their land and their people.

Little Crow was an astute and eloquent representative. Dr Asa Daniels, a physician who worked with him on the reservation for many years, described him as being "restless and active, intelligent, of strong personality, of great physical vigour, and vainly confident of his own superiority and that of his people'. He was also 'a gifted, ready and eloquent speaker, and in council was always ready to answer any demand made by the government... His appeals in these addresses to the government and to the Great Spirit that justice be done to his people, with his rugged eloquence, the lighting up of his countenance, the graceful pose of his person, and the expressive gestures, presented a scene wonderfully dramatic. He was possessed of a remarkably retentive memory, enabling him to state accurately promises made years before to these Native American Indians by government officials and to give the exact amount of money owing them, to the dollar and cent... He was truthful and strictly honourable in his dealing with the government and traders."

He was also fearless. When the question of the succession of leadership arose after his father died, Little Crow was opposed by his half-brother. Although carrying a gun, Little Crow confronted him with arms crossed, openly challenging him to shoot. He did. The bullet passed through both of Little Crow's forearms shattering the bones of his wrists and wounding his chest and face. A surgeon recommended that both hands be amputated, but Little Crow would not allow this as a leader must have hands. He recovered but his face was permanently scarred and he always covered his deformed arms. His great courage, however, had demonstrated to the tribal elders that he was worthy of being their leader.

Such was the man that came to Washington, DC in a last-gasp diplomatic effort to save a situation soon to spiral out of control. Little Crow was accompanied by other chiefs and headmen of the Upper and Lower Sioux as well as the agent for the Native American Indians, Joseph Renshaw Brown, Rev. Thomas S. Williamson who had a mission and school near the Yellow Medicine (Upper Sioux) Agency (pl. 138), and several traders apparently including Andrew J. Myrick of whom more will be told.

The assembled delegation left the agency on 27 February 1858 and arrived in Washington, DC on 13 March. Their first meeting was with the Acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Charles Mix. Little Crow, dressed in the white calico hunting shirt in which he was photographed, started the proceedings by saying, 'Your good advice has reached our ears, we listened and heard what you said... We have business to transact ... we will tell you what we came for.''

Another delegate, Mazaomani, expressed the general feeling of the delegates, 'I am pleased to stand here today, in your presence, in my Great Father's country. I understood if I came here, that any thing I wanted, I would get, and I therefore feel that it is a great thing for my people that I am here,' to which the Commissioner responded, 'say to the delegation that their Great Father never withholds anything that is just from his red children, that his only desire is to benefit them, and promote their welfare; that, if they do not attend to his advise, and take advantage of his efforts to serve them, it is their own fault, and not his, and that it is the intention of the Great Father to be not only just, but generous to them.'

With these statements, the proceedings began. The first real meeting with the Commissioner began on 27 March. Little Crow started the negotiations by reminding the Commissioner that they had never been fully paid for their land: 'In 1858, their Great Father sent a commissioner to treat with them to Mendota, and a treaty was made, and that said he is the reason our people ought never be poor... Of course our Great Father has plenty of funds belonging to us in his hands, and it takes plenty to enable a person to act like a man and not like a poor beggar." The Commissioner responded, 'say to them that, as a people, as a band, they have a large fund at the disposal of their great father...and that it is the purpose of the great father, to apply it as the treaty stipulates. The time is near at hand, when their great father will forward for their use provisions, blankets and other things intrusted for their comfort and support.'

Further he asked Little Crow how he intended to spend the money should it be given to him. I will tell you... We have stores in our country, and we have families to feed and clothe; and, when we return to our homes, we will lay out the money for the support of our families, and buy what we want. This is what we intend to d get." The next meeting did not occur until the middle of April.

Little Crow began that meeting by explaining why his people were hungry and predicted that they would starve again in the coming year: 'Last winter we were badly off, but it was because, in compliance with your wishes, we went in pursuit of Inkpadutah, (a renegade who had massacred settlers) and neglected our corn fields. The land upon which we ought to have planted corn was neglected on that account... I said that our going after Inkpadutah would involve us in want; and now that, by your kindness, I stand here, I hope you will not keep us long, because if you do we will be too late to attend to our planting, and our people will suffer again from the same cause.'10

He continued, 'Twenty-one years ago Wabashaw, the father of these young men, and my father placed in writing on this table, and the promises made in this writing, I have come here to see about. The good advice you then gave to my father and his children entered into our ears, but a portion of the promises made to us have not been fulfilled.' He then listed sums of money due, schools, horses, cattle and even blankets that did not arrive. The list was so long that Little Crow felt it would take all night if he went into more detail. 'All things of which we speak have fallen short of the promises made, or well of [sic] our reasonable expectations... I will sit down, and smoke, and listen to your words; and, after I hear you, will know whether my tribe will be benefitted or not.'12

The Commissioner agreed to look into these allegations but as to the money, it'is safely kept in the strong box of the Treasury, and the reason it has not been paid is, that it could not be expended to their advantage. When the proper time occurs, it will be expended to their benefit.' In addition to provisions and funds not being received, the Native American Indians also complained about settlers moving into lands they still believed they owned. The Commissioner reminded Little Crow that he had signed away these lands to the government and if there was a problem it was Little Crow's fault for making the agreement.

The Native American Indians had to wait until the end of May for their next meeting. Commissioner Mix addressed the issue of title and boundaries of the 1851 treaties first: 'In respect to the treaty of 1851, and of their understanding of the clause giving the president authority to mack [sic] the boundaries... I propose on behalf of their Great Father, to assign to them as a permanent home the South and West part of their Reserve, dividing it by the River.'14 In other words dividing the small portion of the land left to the Native American Indians, and still not paid for, in half. In addition, the small section of land that would be theirs would be divided into farms and allotted to the Native American Indians in severalty.

In early June the Native American Indians countered the proposed government treaty with one of their own which included an unstated amount in appropriations. When the Commissioner asked Little Crow to state a sum of money that would be acceptable to settle their affairs so that the proposal could be taken to the president, he was not prepared to do so. Another pertinent section dealt with funding that was owed to the traders. Little Crow was willing to set aside $50,000 against their rightful debts assuming that this money would come out of the large amounts of money already due to them. The Commissioner agreed but the funds would have to come out of the proceeds from the sale of more of their land.

By mid-June a final treaty was prepared by the government which allowed for the sale of half of the land, the price of which would be set not by the Native American Indians but by the Senate. In addition, a sum of money to be determined by the Native American Indians themselves representing the amount they felt was owed to the traders would be included and further, a consolidation of past annuities would be placed under the control of the Secretary of the Interior for the purchase of food and tools as needed by the Native American Indians. Little Crow was of a mind to leave without signing any papers since in all the treaties they had made, none had been carried out in good faith, to which the Commissioner responded,'... you may go home as soon as you please... but you must recollect that the entire responsibility of breaking off negociations [sic] so beneficial and so necessary to the security and protection of your people, will rest alone on your own head,' he then went on to state one fact Little Crow knew to be true, 'If you don't like it, you can go home, and you will find that the whites will take from you by force, what your Great Father proposes to buy and pay for.'

On 19 June, the Sioux had little choice but to sign the treaties. On June 21 they were given medals as evidence of their good conduct, guns for 'procuring game for subsistence, but never to be used against white men,'16 and told that the president and congress would make proper appropriations and take care of them.

Little Crow had tried to send many letters to the president telling him of problems on the reservation but was convinced that none of them were ever received let alone mailed. He made one final attempt at discussing these problems, but the commissioner would not listen. Little Crow and the rest of the delegation departed the capital empty handed and with little faith in what had transpired. By the time they got home it was late in the year for planting.

For the land ceded by the 1851 treaties, the Native American Indians were promised a total price of $3,075,000 but that was held in trust and only the interest of five per cent a year was to be paid for a term of 50 years at which time the principal was to revert to the government. The amount paid immediately was $555,000, $210,000 of which was allowed to the traders, 17 and the interest, which amounted to $126,000 yearly, was paid partly in provisions with only $70,000 actually being paid in cash.

It took congress two years after the 1858 treaty to set the price for the additional land it acquired. Although valued between $1 and $5 an acre, the price set by congress for the additional million acres amounted to approximately thirty-cents per acre. After traders' claims, which were neither set nor approved by the Native American Indians as agreed by the treaty, the Sioux received about half what had been voted.18 Annuities were due in late June or early July which was especially important in 1862 after another winter of near starvation. They were late, however, because congress waited to appropriate the funds and then spent a month discussing whether to pay in paper currency or gold coin. The much needed money did not reach St. Paul until 16 August by which point it was too late.19

As more and more settlers expanded westwards and railroads started to criss-cross the country, the US government had a difficult situation on its hands. What to do with the Native American Indians? Theories ranged from annihilation to 'civilisation', with the latter being espoused in treaties. A civilised Native American Indian would have no need to millions of acres over which to roam and hunt, nor would they require annuities and rations to replace buffaloes. They could farm and become self-sufficient, enjoying the riches of settled society. Native American Indian delegations to the East were always treated to a display of the riches that could be earned by adopting this foreign life style. At the same time they were also shown demonstrations of military

sheer size of the cities and the number of the people, the underlying theme was always that it was better to join than to fight. In Little Crow's own words, 'We are only little herds of buffaloes left scattered... the white men are like the locusts when they fly so thick that the whole sky is a snow-storm. You may kill one - two-ten; yes, as many as the leaves in the forest yonder, and their brothers will not miss them. 20

Thus with guidance and some equipment, some Native American Indians tried farming. Indeed, some agents for the Native American Indians made annuity payments only to those Natives who would cut their hair, wear white clothing and farm. They became known as 'farmer' Indians whereas those who kept their traditional lifestyle were known as 'blanket' Indians.

While the new Native farmers met with some success, to survive, many had to turn to Indian traders, purchasing food on credit while they waited to be paid by the US government.

Combined with the inflated figures supplied by the traders, most, if not all of the money received for their lands went directly into their pockets leaving the Native American Indians unable to purchase more food or provide for themselves. Those Native American Indians who chose to hunt instead of farm still had sufficient hunting areas within the reservation, but encroaching settlers frequently hunted in these regions and either drove away or killed most of the game leaving the 'blanket Indians' starved as well.

It was against this backdrop that events rapidly moved to an unavoidable encounter between the Native American Indians and the settlers in what was to become one of the bloodiest massacres in American history.

In July and August several thousand Native American Indians had come to the Upper Agency to find out why they could not be fed from the warehouse full of provisions that belonged to them. The Agent relented and distributed a few goods, but clearly that was not enough. Meanwhile at the Lower Agency provisions due in early June had still not arrived. Little Crow demanded that the traders further extend their credit so they could eat but they refused. Andrew J. Myrick, one of the traders who came from Washington, DC, further inflamed the situation by remarking, 'If they are hungry, let them eat grass.'21

Starved from failed crops, loss of game and the lack of annuities; frustrated by broken promises, squeezed into ever smaller tracts of land and financially unable to buy their way out of the situation, the Native American Indians were in an explosive situation that needed just a spark to set things off. That spark occurred on 17 August. The incident was recounted by Big Eagle one of the 'farmer' Indians at the Redwood Agency:

'You know how the war started by the killing of some white people near Acton, in Meeker county. I will tell you how this was done, as it was told me by all of the four young men who did the killing. These young fellows all belonged to Shakopee's band... They told me they went over into the Big Woods to hunt... they came to a settler's fence, and here they found a hen's nest with some eggs in it. One of them took the eggs, when another said: "Don't take them, for they belong to a white man and we may get into trouble." The other was angry, for he was very hungry and wanted to eat the eggs, and he dashed them to the ground and replied: "You are a coward. You are afraid of the white man. You are afraid to take even an egg from him, though you are half-starved"... The other replied: "I am not a coward. I am not afraid of the white man, and to show you that I am not I will go to the house and shoot him. Are you brave enough to go with me?"... They all went to the house of the white man, but he got alarmed and went to another house where there were some other white men and women. The four Native American Indians followed them and killed three men and two women.

After murdering the five people, they went to Sha-kpe's camp and told what had happened. The members of the soldier's lodge debated what should be done, ultimately deciding to fight the encroaching whites and reclaim their lands. Sha-kpe' then took them to Little Crow, who knew that fighting would bring disaster. First he tried to bring them to their senses, 'You are full of the white man's devil-water. You are like dogs in the Hot Moon when they run mad and snap at their own shadows, and then reasoned with them about the futility of trying to outfight the whites. Their response was to call him a coward, to which he replied, 'You will die like the rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them in the Hard Moon (January). Ta-o-ya-te-du-ta (one of Little Crow's names) is not a coward: He will die with you'.24 The next day Little Crow led the first assault on the Lower Agency at Redwood.

Some of the events that occurred were recorded in text and images by a little-known frontier photographer by the name of Adrian J. Ebell. Ebell was accompanied on his photographic expedition by Edwin Lawton, a student. Lawton's diary tells of their 'Phantasmagorical Exhibitions' (lantern-slide shows), and their adventures to the Upper Missouri region photographing the Native American Indians and scenery. Along the way they encountered immense swarms of mosquitoes, thunder storms with torrential rains, and axle-deep mud. Their travels took them through the Lower or Redwood Agency where Lawton saw his first Native American Indians. Beyond that they passed Little Crow's village, and 'several civilised Indian houses where the squaws are engaged in the fields seated on a platform raised up above the top of the grain (commonly corn) engaged in the very interesting occupation of scarecrows to frighten off the black-birds from the grain'.25 Lawton or Ebell photographed these women scarecrows (pl. 137) which was later circulated by Whitney, as well as Indian women winnowing wheat.

Their ultimate destination, however, was the Upper Agency at Yellow Medicine. Lawton's entry for 13 August reads, ... met two companies of soldiers, then but a few miles ahead of us, on their way back from the Upper Agency, whither they had been to subdue a disturbance among the Native American Indians, who getting unruly had attempted to break open the government warehouse."26 His last entry is dated 15 August and reads,'... We rested half an hour, and then started on our way again anxious to see our place of destination the long expected 'Upper Agency'.27 Little did they realise what lay ahead for them.

Ebell recounted much of the tragedy in the June 1863 issue of Harper's New Monthly Magazine. The massacre started after midnight at the Lower Agency and spread like wildfire. Once the signal had been given the Native American Indians broke into the stores and warehouses. While the women carried off the food, the men attacked the people. The first to die was a clerk at the store of the hated trader, Andrew Myrick. Myrick himself managed to escape from a second-story window, but was killed before he could reach cover. His corpse was later found with grass stuffed in his mouth - a reminder of his harsh words. 'Some were hewed to pieces ere they had scarce left their beds... But who can tell the story of that hour? Of the massacre of helpless women and children, imploring mercy from those whom their own hands had fed, but whose blood-dripping hatchets the next moment crashed pitilessly through their flesh and bone of the abominations too hellish to rehearse of the cruelties, the tortures, the shrieks of agony, the death-groans, of that single hour? 28

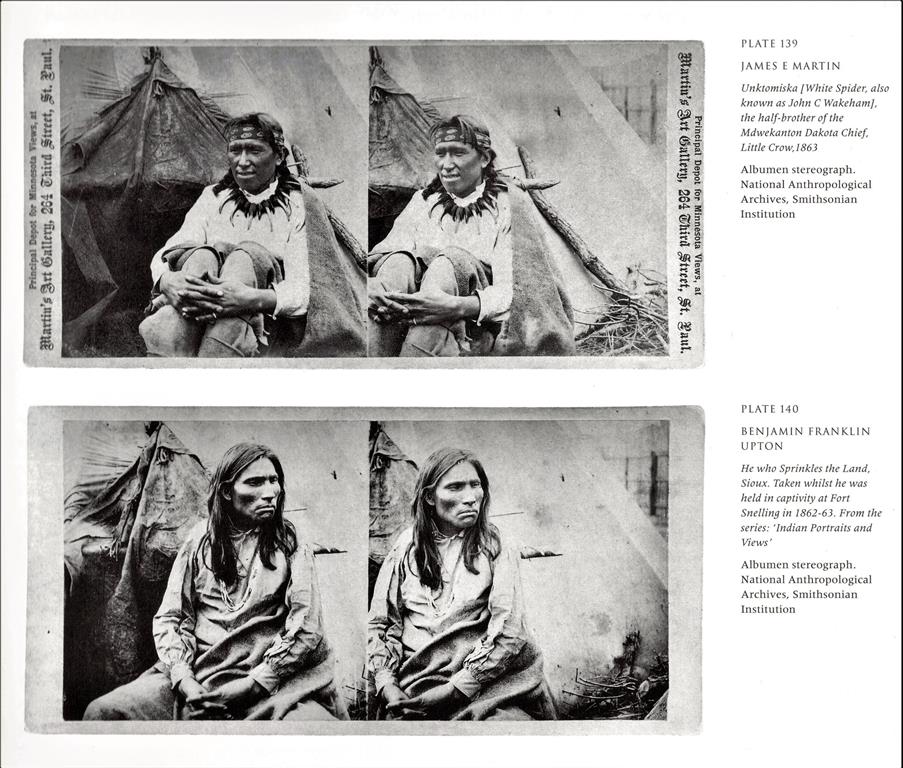

A village of several thousand people formed around Little Crow's house including over three hundred captives. Some of the Native American Indians, even Little Crow, not only felt compassion for the captives but also sheltered and saved many of them. White Spider, (pl.139) told how Little Crow, his half-brother, instructed him to gather up what white women and children he could and guide them to safety. I had no moccasins on my feet, but I went a long way. I went seven miles... the Little Crow kept a good many of the captives in his own home, and treated them the same as he treated his own children, and had them eat with him. 29

Those that did escape spread the alarm. The Native American Indians followed the entire line of settlements over hundreds of miles committing unheard of atrocities. Cut Nose (pl.92) and two others leapt into a wagon of fleeing settlers, mostly children, and tomahawked them all.

One infant was taken from its mother's arms, before her eyes, with a bolt from one of the wagons, they riveted it through its body to the fence, and left it there to die, writhing in agony. After holding for a while the mother before this agonising spectacle, they chopped off her arms and legs and left her to bleed to death.

Narcis Gerrian, a settler, leapt from the window of the mill to the river. Before he reached the water he was shot twice in the chest. He managed to swim across, almost drowning and then dragged himself through woods and swamps for sixty-five miles without food, before being rescued.

Over five-hundred settlers sought protection from the military at Fort Ridgley, which was itself doomed as there were only thirty soldiers, few arms or ammunition and little provisions. In the meantime people at Yellow Medicine were unaware of the approaching danger. On Sunday 17 August, Ebell took a photograph of the missionary Thomas S. Williamson and some of the farmer Native American Indians outside the mission house (pl. 138).

Ebell recounts the flight of forty unarmed people including Dr Williamson, the physician, and Stephen Riggs, the missionary. A war party tried to follow them but fortunately a thunderstorm obliterated their tracks. Meeting other fleeing settlers they learned of many horrors. They had no provisions and the rain, at first a saving grace, continued through the night. 'It is easy for one to keep up courage when his blood is warm; but in a half freezing, drizzling rain, trickling drop by drop through the clothes, and seemingly to the very bones, lying in a puddle of mud and water, courage, if it exist, is truly a genuine article.

The next morning, 21 August, they drove through mud, crossed streams with difficulty, and finally stopped for '... our only chance for breakfast... we killed a calf, and at about three in the afternoon had our breakfast of partly roasted or smoked veal'. Ebell photographed them while they stopped to eat (pl.136). This amazing image is the only photograph known to have been taken during the flight of the settlers.

The little group's path took them past scenes of massacre and plunder but somehow they managed to escape the Native American Indians and eventually were in sight of Fort Ridgely. A rocket from the fort, meant as a distress signal, was interpreted as a beacon to guide them. They finally managed to reach the fort only to be told that they could not be accommodated as hundreds of other settlers were already there and they would have to move on. They were not alone.

The entire population of approximately 40,000 settlers from Fort Ridgley, New Ulm, and the Norwegian Grove, almost to St. Paul, fled panic-stricken as wave after wave of massacres occurred. Some, including Ebell and the little group of settlers made it to safety. Soon after they were turned out of Fort Ridgely it was attacked and could not be defended. Attacks continued for eight weeks, until the Native American Indians were eventually outnumbered and outgunned by the military led by Henry Sibley.

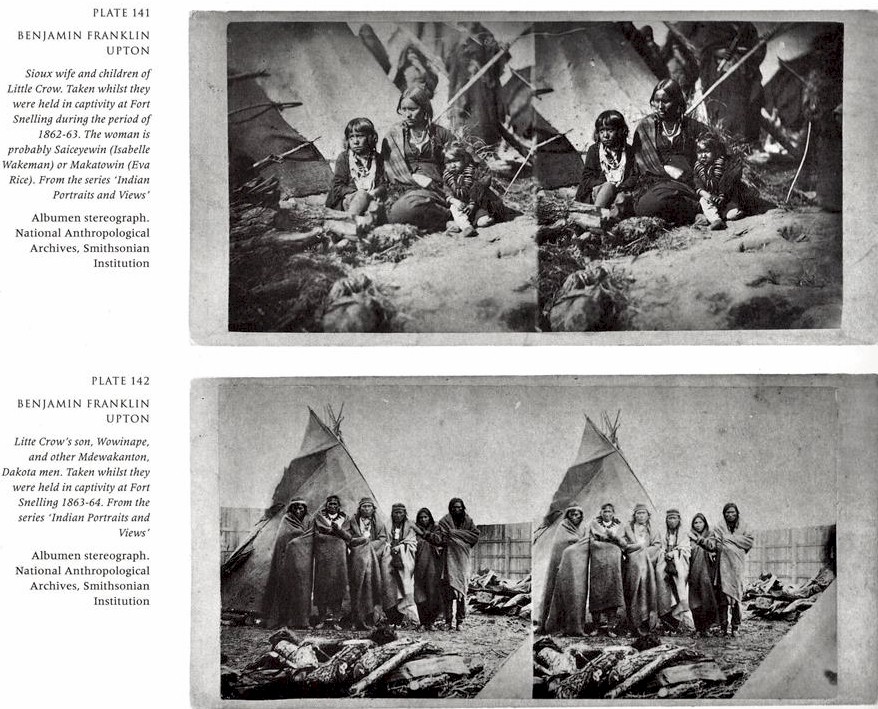

Four thousand Native American Indians then fled to the West, and to the North into Canada including Inkpadutah, Little Crow and his son, Wowinape, Sha-kpe' and Medicine Bottle. The remaining two thousand Native American Indians, mostly women and children, were force-marched to prison at Fort Snelling forming a four-mile long line. Along the way the settlers stoned, clubbed, and stabbed them with pitchforks.

A military commission tried 392 Native American Indian prisoners in a log-cabin courtroom at the Lower Agency. Of these, 307 were sentenced to death and moved first to Camp Lincoln and then to a make-shift prison at Mankato. The names of the Native American Indians found guilty were sent to President Lincoln for approval of a death sentence. Not wishing to make a hasty decision he was, 'anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand; nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I caused a careful examination of the records of trials to be made [to determine) who were proven to have participated in massacres, as distinguished from participation in battles'.4 On 6 December, he approved the death sentence for only 39 of the prisoners, one of which was later respited. On 26 December, the 38 prisoners were hanged at Mankato, in the largest mass hanging in American History.

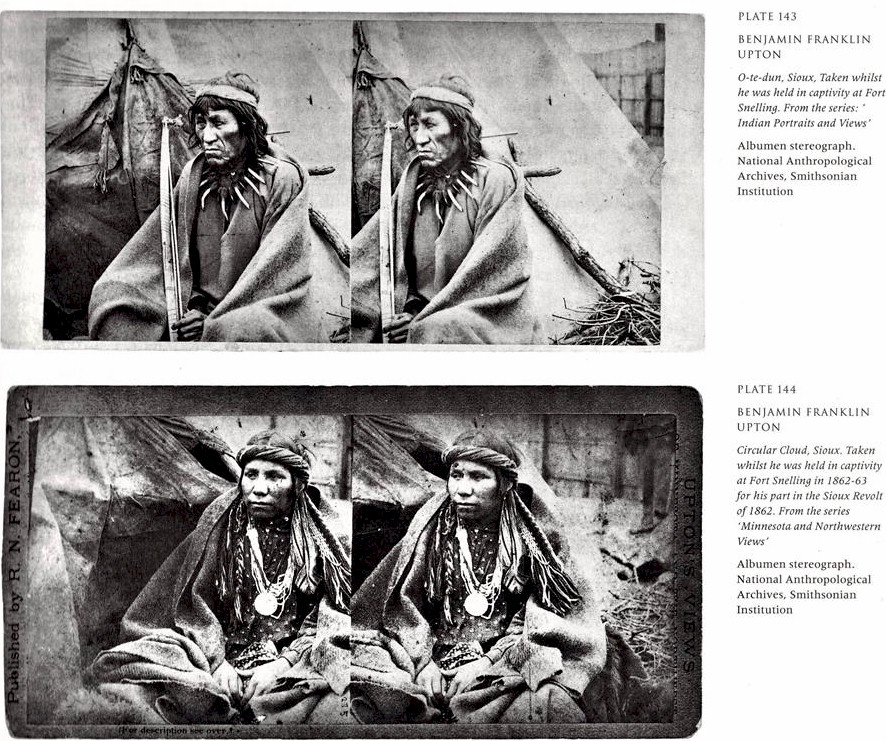

The remaining 1,700 Native American Indians were placed in a fenced enclosure at Fort Snelling where they lived in tipis for the remainder of the winter. (pl. 139-144) Lacking sufficient food and heat, an additional 300 died that winter.

In the meantime, Little Crow and Wowinape, his son, were in Canada trying to enlist British help while the US government placed a bounty on all renegade Native American Indians. In the summer of 1863 Little Crow and his son returned to Minnesota. On 3 July while picking raspberries, Little Crow was shot by Nathan Lamson who was also in the patch with his son, Chauncey. Wary of all Native American Indians and interested in obtaining the bounty money, Nathan shot the elder of the two without knowing who he was.

Wowinape later recounted the event. His father had been shot above the hip and returned fire. He was then shot a second time and realising that he was mortally wounded whispered to his son for a drink of water and then died." The boy then dressed his father's feet in new moccasins, covered the body with a blanket and left to find food and shelter for himself.

The people of Hutchinson brought the unidentified body into town and left it lying in the middle of the street. Boys celebrated the Fourth of July by placing firecrackers in the ears and nose. Lamson collected the $75 bounty and although rumoured to be Little Crow, identification was not possible as the head had been scalped. The local doctor buried the body and although the torso disappeared, he later retrieved the skull and arm bones which showed the massive damage done many years earlier and established the identity of the body.36

Wowinape wandered around nearly starving to death until captured twenty-six days after his father's shooting. He was sent to prison where he learned to read and converted to Christianity. Eventually he was pardoned and became active in the local Presbyterian church, devoting the rest of his life to the development of a Dakota Indian YMCA.

Sha-kpe', another of the proud diplomats who had once negotiated with the USA, and Medicine Bottle (pl.158) also fled to Canada. They were eventually captured, drugged and smuggled across the border on dog sleds and brought to Fort Snelling in 1864. Their execution took place on 11 November 1865 at the site where the Mendota treaty of 1851 had negotiated away much of their land.

The tragic story of the 1862 Sioux revolt was documented by several photographers. At one end of the scale are the elegant portraits made before the revolt in Washington, DC by the McClees studio such as those of Little Crow, Sha-kpe' and other diplomats. The works by Adrian Ebell and Lawton show a world just before and during destruction. At the other end of the scale are the haunting portraits made by Benjamin Upton, James Martin (who later formed a partnership with Upton), and Joel Emmons Whitney (later Whitney and Zimmerman) of the prisoners in their captivity at Fort Snelling. Some of the portraits made were of Little Crow's half-brother, White Spider, (pl.139); one of Little Crow's wives and some of his children (pl.141), and his son Wowinape with other imprisoned Native American Indians (pl.142). Some of the most poignant are those of former diplomats such as Sha-kpe' before they were to be hanged (pl.97). Native American Indians remembered for their assistance to the settlers were also photographed such as Old Bets (pl.93) and John Other Day, another of the 'farmer' Indians living near the Upper Agency who organised and led a party of 62 people to safety.

Once their histories are known, these images speak for themselves. We do not know what either the photographers or the subjects were thinking or feeling when these portraits were made. I suspect they were pretty straightforward reactions. While we must explore the deeper nuances of images and how they are used, we must remember that once these were real people in very real situations. It is critical that we do not forget to tell the rest of the history.

NOTES

1 Santee Upper and Lower Sioux together; Upper Sioux = Wahpeton and Sisseton: Lower Sioux = Mdewakanton and Wahpekute.

2 Asa Daniels, Reminiscences of Little Crow', Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 12, 1908, p.514.

3 Daniels, 'Reminiscences of Little Crow', 1908 pp.517-18.

4 "Sioux Delegation from Minnesota in the Indian Office Documents Relating to the Negotiations of Ratified and Unratified Treaties with various Indian Tribes (hereafter, Documents). National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), microfilm (mf) T494, 15 March 1858, p.7.

5 Ibid., p.8. 6 Ibid., p.9.

7 'The Sioux Native American Indians from Brown County Minnesota', Documents, NARA mfT494, 27 March 1858, p.2.

8 Ibid., p.3. 9 Ibid., p.4.

10 'Sioux from Brown County, Minnesota in Indian Office, Documents, NARA mfT494, 9 April 1858, pp.1-2.

11 Ibid., p.2. 12 Ibid., p.4. 13 Ibid., p.5.

14 'Medawahkanton and Wahpekotay Sioux,' Documents, NARA mf T494, 25 May1858 p.2.

15 'Lower Sioux Treaty Meeting.' Documents, NARA m'fim. T494, 19 June 1858, p.7.

16 'Delegation of the Lower Sioux. Final Interview,' Documents, NARA mfT494, 21 June 1858, p.1.

17 Gary Clayton Anderson, Little Crow: Spokesman For The Sioux Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1986, pp.64, 68-9.

18 Kenneth Carley, The Sioux Uprising of 1862, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1961, p.13.

19 Ibid., p.14.

20 Anderson, Little Crow, 1986, p.132.

21 Carley, The Sioux Uprising, 1961, p.15.

22 Big Eagle, 'A Sioux Story of the War,' St. Paul Pioneer, 1 July 1894; repr. In 'Chief Big Eagle's Story of the Sioux Outbreak of 1862.' Minnesota Historical Society Collections, Vol. 6. 1894, pp.388-9 and Anderson and Woolworth, Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988, p.35-6.

23 Anderson, Little Crow, 1986, p.132.

24 Ibid., p.132.

25 'Diary Journal of E R Lawton, 1862.' p.100. Original ms in Minnesota Historical Society.

26 Ibid., p.82.

27 Ibid., pp.109-10.

28 Ebell, The Indian Massacres and War of 1862, Harper's, Vol. 27:157, June 1863, p.8.

29 White Spider, quoted in Anderson and Woolworth, Through Dakota Eyes, 1988, pp.61-2.

30 Ebell, The Indian Massacres', 1863, p.9.

31 Ibid., p.9. 32 Ibid., p.12. 33 Ibid., p.13.

34 'Lincoln's Sioux War Order, Minnesota History, Vol. 33:2, 1952. Pp.77-8.

35 'Statement of Wo-wi-nap-a: translated by Joseph De Marais, Jr.' St. Paul Pioneer, August 13, 1863; quoted in Anderson and Woolworth. Through Dakota Eyes, 1988, p.280.

36 Anderson, Little Crow, 1986, p.8. The scalp, skull and arm bones were deposited in the Minnesota Historical Society where they were placed on exhibit.